In comparing design to dialectics, we explored whether the famous “double diamond” is really how design works, arguing that, no, it probably isn’t. This of course raises the question of just how design works. The answer, unsurprisingly, depends on what is meant by “design”. In this post we will look at the work of design theorist Kees Dorst for an answer. For Dorst, design is very specifically about framing.

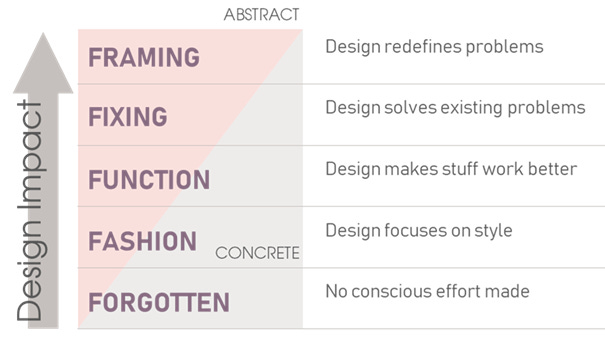

For Dorst, when teams build what is asked of them, that is solutioning, not design. Design proper is more about rejecting self-diagnosis, surfacing assumptions, and reconfiguring the context itself to produce new thinking. In what is probably my favorite take, my friend Jess McMullin shows this as a range depicting design impact.

Reframing a situation requires a certain amount of decision authority. When such authority is withheld, interventions will be confined to lower levels of impact. Thus, it is only when given the authority to reframe the context that design proper can occur. If it is rare that teams are given carte blanche, then true design work will be rare. This also means, incidentally, that risk taking and innovation will be rarities, as the status quo approach will be inside-the-box solutioning and execution to plan with a likely focus on speed.

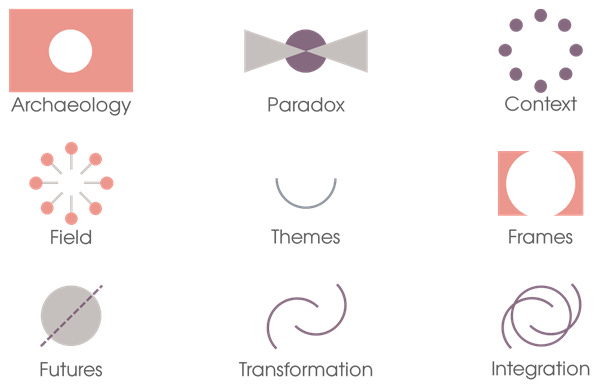

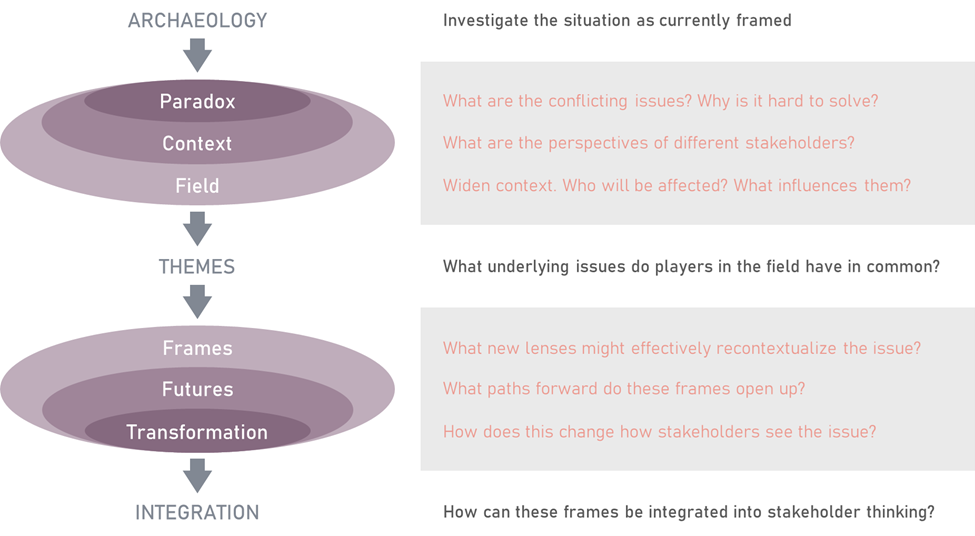

When given carte blanche, what does real design look like? In Frame Innovation, Dorst argues that designers tend to go through nine essential steps. We’ll take a quick look at each and how they tie design specifically to the task of optimizing decision frames. The nine steps (or moves or focus areas) are Archaeology, Paradox, Context, Field, Themes, Frames, Futures, Transformation, and Integration.

Archaeology

The first step is about surfacing and optimizing assumptions. What is the current situation? What have people already tried? Who owns the problem? (They have in some ways helped to shape the situation as it is.) What can be changed? What are nonnegotiables? What decisions are on and off the table?

Let’s say a request is coming from a team (we’ll call them the “customer”) who takes graphs from an existing dashboard and uses them to present to executives. The executives have given feedback that the graphs are confusing. If the dashboard was customizable, the customer reasons, then they could more easily create different data displays.

Paradox

Once the actions that have shaped the problem situation have been explored, it is time to turn to an initial frame of the problem itself. Where is the deadlock? Dialectically, the “paradox” is the core conflict, the clash of rationalities, agendas, and entangled issues that make the situation seem intractable. Dorst recommends representing stakeholder rationales as a series of “because” statements. This doesn’t have to be a true “conflict”, as the language suggests, but can simply summarize the various stakes of the main problem owners.

For example, “Because the execs want someone to brief them, they have others take graphs from a dashboard and present them in a meeting.” “Because the execs find these graphs confusing, the customer wants a better way to generate data visualizations.”

Context

Here the core paradox is placed aside (for now) and attention turns to other stakeholders. Who else is involved in this situation? Aside from the problem owner, who are the other key players? What have they tried? How do they think of and describe the situation? In other words, what are their frames?

In our example there are the executives in the decision meeting and the customer team who is asking for the dashboard to be made customizable.

Field

Now expand to the wider field and consider all potential players. Who else is involved? How might they have tried to influence the situation? What is their perspective and power related to the matter at hand? Who else has been impacted by this situation and previous attempts to address it? What are their perspectives?

Expanding the field here, it turns out the decision meeting in question is a regularly occurring multi-hour affair with a bunch of attendees who do not really need to be there. Further, every time the meeting occurs hours of work from multiple teams goes into updating the dashboard.

Themes

What are the larger themes that underly the needs and experiences of this wider cast of players in the field? Of these, which do the players or stakeholders have in common? Which pertain to the problem situation on a deeper level? These are your “universal” themes you will then carry forward.

Talking to the teams doing this legwork reveals that kludging this data together includes no small amount of guesswork. There is an overwhelming amount of overhead associated with this meeting, with multiple stakeholders strongly questioning its overall value.

Frames

Here you explore the common themes that might serve as a launching point for frames that will be of interest to a wide network of stakeholders. A frame offers a new lens, a new metaphorical way of configuring the situation that suggests certain paths forward.

After a series of stakeholder interviews it becomes apparent that the crux of the issue across the players in the field is not the dashboard but the meeting itself, which is generally not thought of as a good use of anyone’s time.

Futures

Develop your frames and suss out their viability. This helps with the generation of future scenarios suggested by the adoption of a specific frame. The “fitness” of a frame should be assessed by the interest and commitment sparked in interested parties.

In our example, is there a way to design a future where the need for this burdensome and expensive meeting is done away with?

Transformation

Critically evaluate the feasibility of chosen frames, assessing their utility in conversations with parties in the field. Some frames may be dropped for a lack of feasibility, whereas others will be evolved to make them stickier and more actionable. The output of this step is a transformation business plan for achieving results, both in the long and short term.

It turns out the executives also question the value of the decision meeting. Further, the people who kludge the data together for the dashboard even question its predictive value. It’s more those presenting to the executives who want the meeting to continue. It gives them executive access they wouldn’t necessarily have otherwise.

Integration

The frames that emerge will likely involve new thinking, which may change how things are conceived and done among partners in the field. For these frames to be successful, then, they must be “owned” by these parties. “Integration” here means the shifts in thinking generated by this process are embedded in and change the discourse in the involved organizations, becoming a part of their active knowledge.

The executives are fully on board with doing away with the meeting, as are the teams who do all the legwork to maintain the dashboard. The customer team agrees the existing process is inefficient. The unexpected outcome of this process is a future scenario that does away with both the dashboard and the meeting, replacing both with a decision process that does not involve either.

In close, one thing to note is that Dorst’s terminology leans heavily on seemingly “intractable” issues. The real point, however, and hopefully the example used helped make this clear, is that the proper focus of design is to produce new ways of seeing the issue at hand. This, quite interestingly, is a take that makes design highly similar to the field of Decision Quality, in that both are chiefly focused on frame optimization.

Until next time.