Getting Serious About Results

It’s often said that OKRs are not any better than MBOs. I’m afraid it’s worse than that. MBO, after all, never stood for “Management by Output”. Yet whenever the KR part of OKR devolves into planned output, as it so often does, that is all that orgs are left with. OKRs were supposed be a strategy dissemination tool that helps with prioritization. They are now time and again used as a workaround when there is no real strategy in sight.

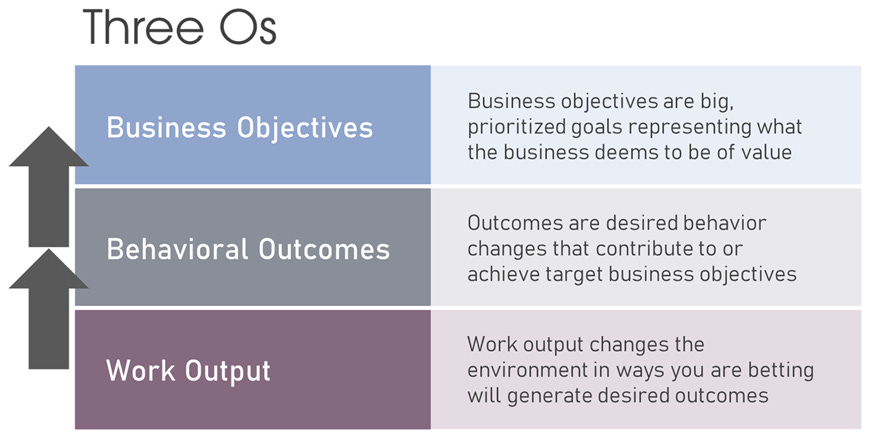

The result is a huge freakin’ mess. It would help of organizations at least took the “Three Os” seriously, a key point of which is that management by output often does not help achieve objectives. What is more, a great many authors have pointed this out over the last decade. Most organizations however insist on pretending that objectives magically flow from sheer output accumulation, like they’re planting acorns and just know to expect oak trees.

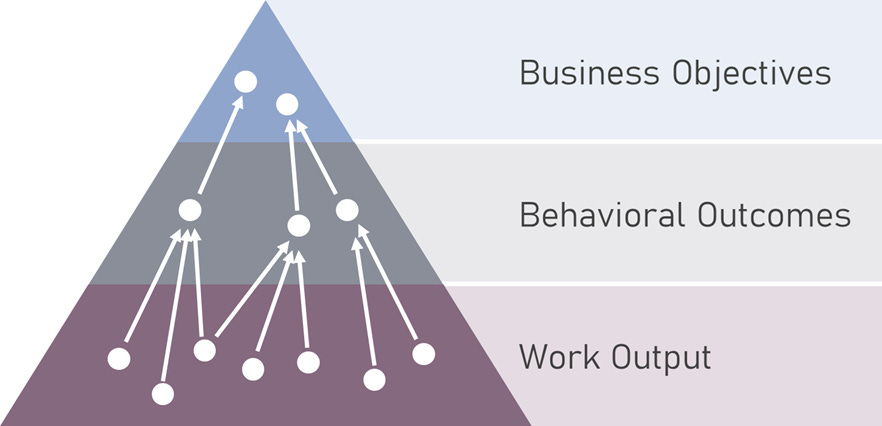

As John Cutler notes, your output, the work you do (or team or org), is more like placing bets. Output velocity is betting speed, not smartness. Work output, whatever it is, changes the environment in some way. In choosing output, you are then betting that a specific change to the environment will generate some specific new, value-adding behavior. This resulting behavior is an outcome.

To create new business value, someone, somewhere, must change their behavior in a way that generates that value—no new behavior, no new value. The desired value is represented as a business objective. This should shift the focus of teams. Output, after all, can be anything that changes behavior in ways that achieve outcomes.

People get all hung up on software products and fetishize coding when output could be a policy change, a process improvement, a workflow redesign…anything. This output, furthermore, could be applied to anyone, whether they be users, customers, fellow employees, clients, constituents, or a single executive. The point is they’re people and the real lever at play is human behavior.

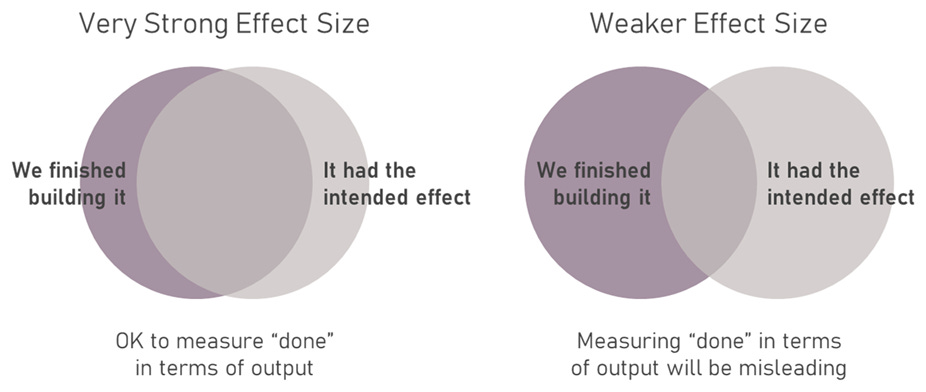

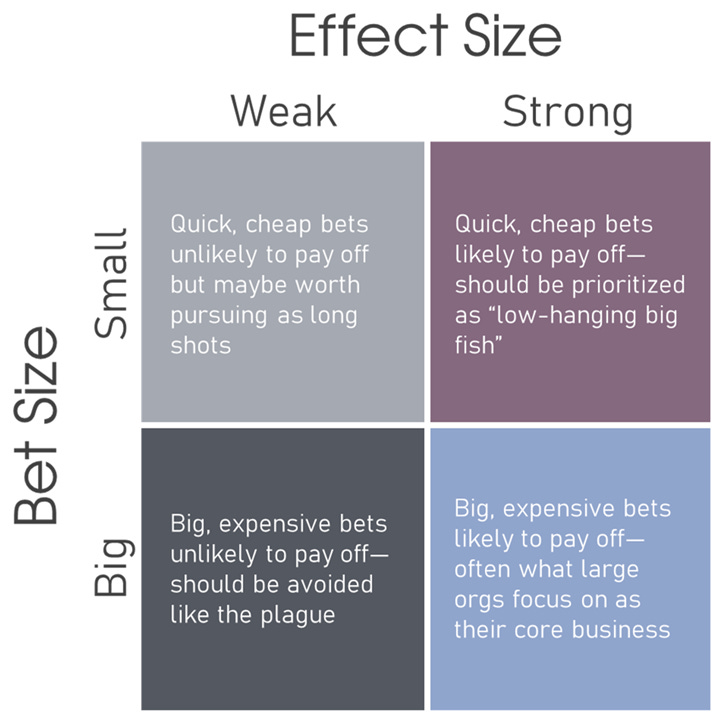

The thing about people is that they’re unpredictable. When you predict that Output A will result in Outcome B, you will only be right some X% of the time. In other words, the correlation between output and outcome will be < 1. Whether measured as r or r squared, in statistics this is called an “effect size”. This is a measure of how predictive one variable is of another.

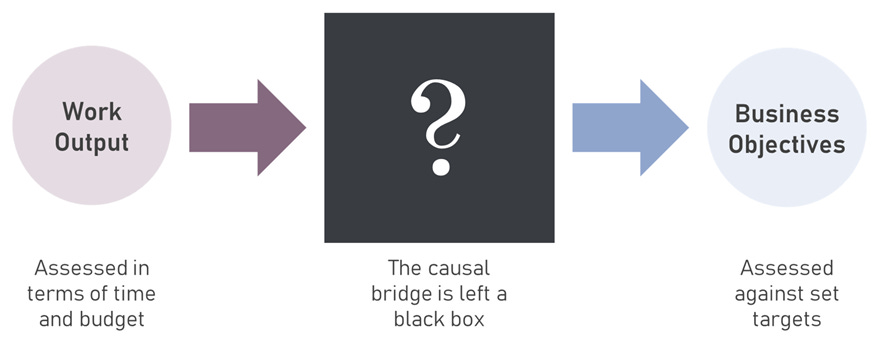

Most organizations do not focus on this. For instance, much has been written about why the majority of projects supposedly fail. Ironically, in most such literature “failure” only means the project wasn’t delivered on time and budget, ignoring altogether the outcome of “successful” delivery. The lone probably of “successful” delivery, no matter how low, ignores the larger reality that conjunctions of probabilities will together be even lower.

To illustrate, let’s call the probability that Output A will be delivered P(A). The probability that Output A will produce Outcome B is then P(A → B). The probability Outcome B will achieve (or contribute to) Objective C is P(B → C). What you’re really interested in is not P(A), which is what most of the literature on this topic is focused on. What you should care about is P(A → C), the probability that your bet helps achieve your objectives.

For the sake of example let’s choose some really high odds. Let’s say there is a 70% chance the chosen output will be successfully delivered, a 70% chance it will produce the desired outcome, and a 70% chance this will contribute to the target business objective. Notice that does not mean that if the output is delivered there is a 70% chance it will contribute to the objective!

What you’re really interested in, P(A → C), is actually .7 x .7 x .7, which = 34%. Taking another example, even if the odds of each were 80%(!), then P(A → C) = .8 x .8 x .8 = about a 50/50 chance. And this is just one small hypothesis chain. Now imagine a behemoth, scaled pyramid. What you’re left with is a giant bundle of risk. What to do?

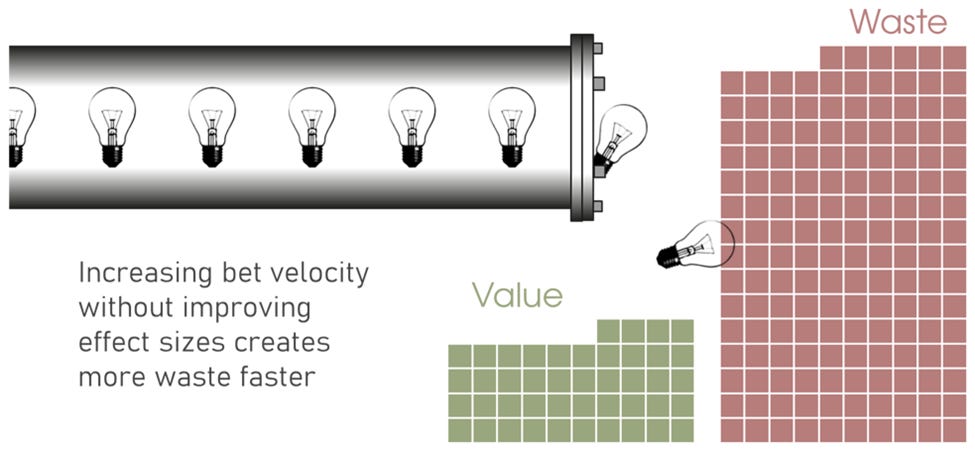

Anything that pulls this bundle apart and achieves outcomes with smaller bets will help. Please notice that without this, all the fuss in the world about “Agile” becomes moot. As Gabrielle Benefield has quipped, all most Agile teams can realistically say is, “Well at least we’re failing fast.”

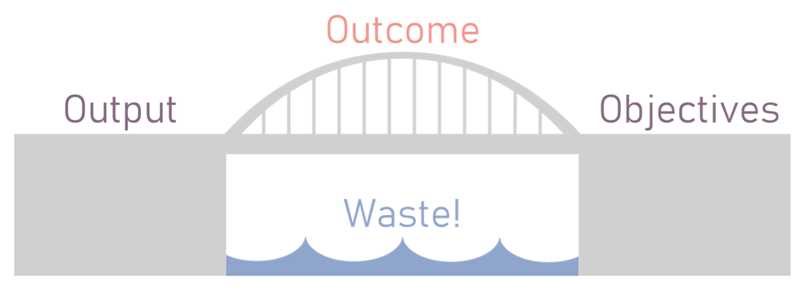

Ignoring outcomes ignores what Tom Kerwin calls “pivot triggers”—no pivot triggers, no real agility. Thus, Agile, properly understood, is about redesigning organizations to have high tactical flexibility. This requires that you rethink traditional “productivity”. As Jeff Patton puts it, your goal should be to maximize outcomes per minimum output. As I have said for years, output generated faster than you can learn is waste.

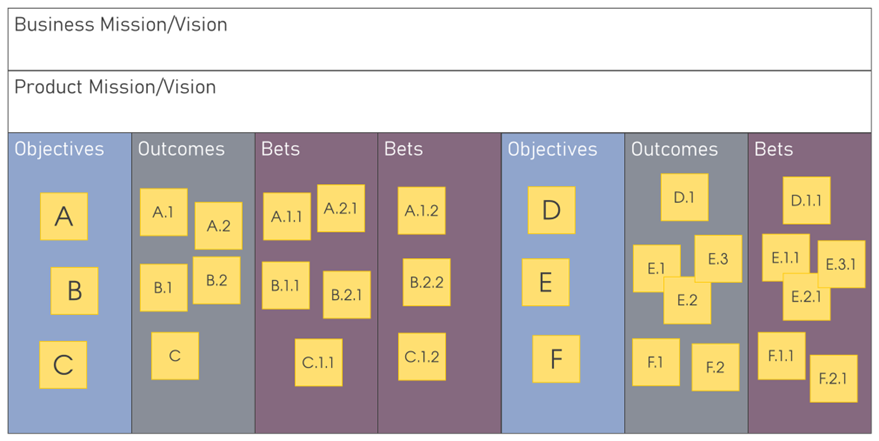

Because of this, the cost of delay of the outcome you’re chasing should matter more than the cost of execution. (If it doesn’t, then why are you chasing it? Seriously, that doesn’t make sense!) OKRs can help here, but only provided that KRs are defined in terms of behavioral outcomes. Instead of output velocity, focus on the efficiency and effectiveness of achieving KRs (actual outcomes). Track them against the advancement of larger business objectives. Stop reviewing them quarterly and use them as an engine to drive rapid experimentation and regular reprioritization.

Further, as Andy Grove stressed, use them to home in, to focus on fewer goals at a time. Consider this example from Neal Whitten. Imagine an executive walks up and asks, “What are your top three priorities at work right now?” Can you name them then and there? Whitten argues that if you cannot quickly rattle them off, on the spot, then you are not an effective leader or employee. Sounds harsh. His point though is that if you need time to identify your priorities, then you do not currently know what they are…which further means you are not using them to prioritize your work.

Furthermore, this is true on a day-to-day basis, which means you are daily focusing on what should be low-priority work. So…what are your top three priority objectives? If you can state them, then unpack them. What outcomes would take the business closer to each objective? How will you know when you’ve achieved them? Prioritize work that moves them forward.

This also means, by the way, that teams should not be committing to build unvalidated planned output and should instead sign up to solve target problems. If you have an output-based roadmap, then start adding outcomes to it. For each item on the output-based roadmap, what outcome is it meant to achieve? (If you cannot say, then why is it there?) Have your team add outcomes on sticky notes and rework the plan as a roadmap of outcomes to achieve in service of prioritized objectives.

This helps shift the focus away from dates to the achieving of business results. Teams should then begin grading themselves, looking at the percentage of outcomes achieved. This will begin to supply you with the information needed to suss out the actual effect sizes at play. You can then use this information to motivate teams to start improving these effect sizes, thereby making smarter bets.

Until next time.