You’ve probably heard of OKRs. They sound like a really good idea. Maybe you’ve even advocated for their use. But be careful what you wish for. It might be a case of, “Better the devil you know”. What was meant to be a lightweight alternative to annual planning ends up being the sneaky return of those dreaded MBOs….

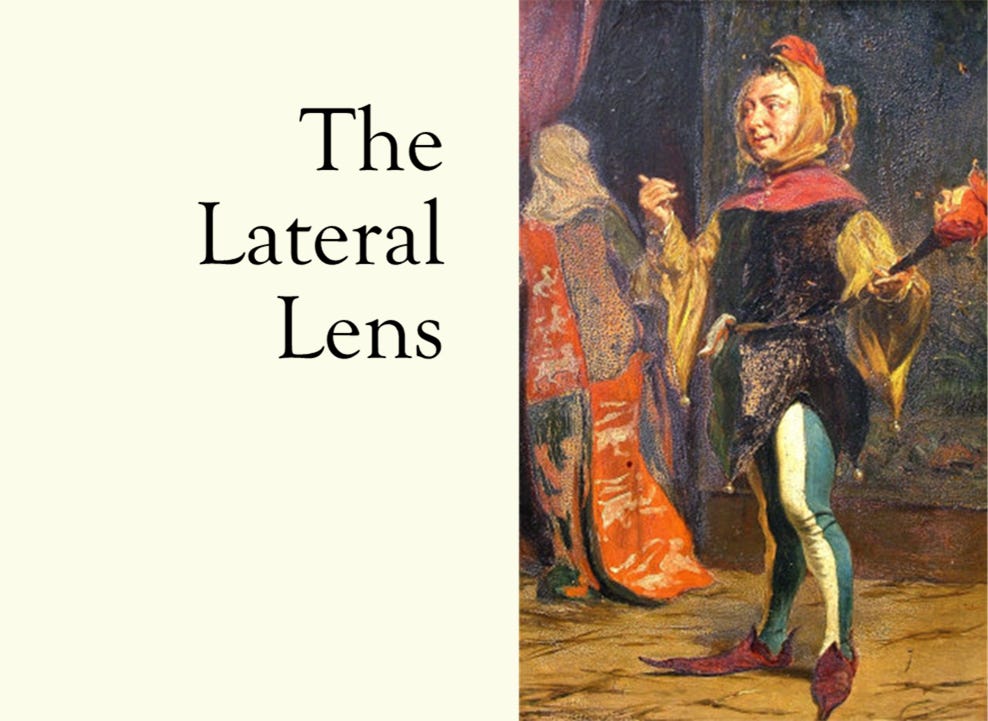

In case you’re not familiar, OKRs originated as Andy Grove’s version of Drucker’s concept of “Management by Objectives”. Grove taught his approach at Intel University in the 1970s. John Doerr, then an Intel executive, learned the practice from Grove and later taught it to the startups he invested in through Kleiner, Perkins, Caufield, and Byers.

The definitions are straightforward enough. Objectives are supposed to be qualitative stretch goals that are short, engaging, ambitious, and inspirational. Tied to each objective are several key results, the KRs, which are quantitative outcome measures used as that objective’s measure of success.

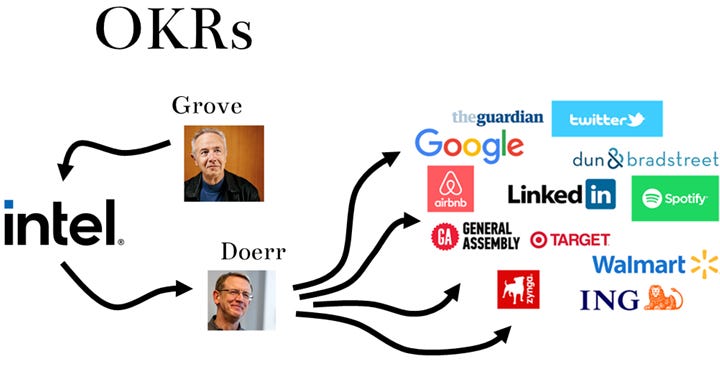

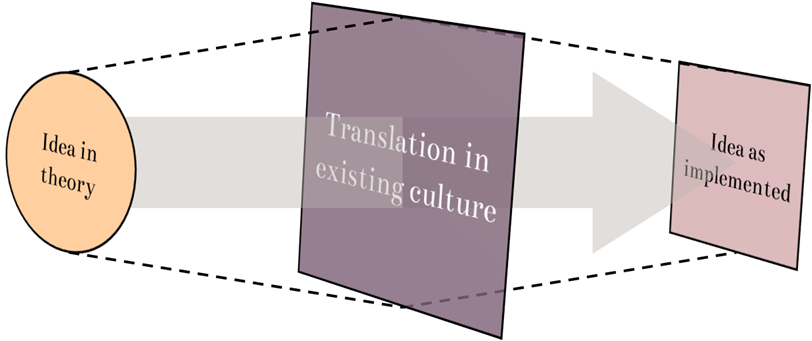

So, what’s the problem? Well, best laid plans and all that. Ideas meant to improve organizations instead get grafted to them. A transformation meant to increase org agility devolves into bullying product teams. The latest attempt to better scale said agility only makes IT yet harder to work with, to the chagrin of the weary business units. Time and again large organizations adopt the latest fad, but then drive them through the prism of their existing cultures. The Borg assimilates.

What we are left with is, well, a mutation. I’ve noticed that OKRs tend to go wrong in three big ways.

1. KRs tend to be glorified task lists

When this happens, KRs tend to focus on output (lists of work to be done) and not outcomes (the difference that work is meant to make). Why does this matter? Consider, the KRs for a given objective are supposed to be its “as measured by”. Thus, in writing an OKR, you are hypothesizing that a certain objective will be achieved when certain specific outcomes are met (its KRs).

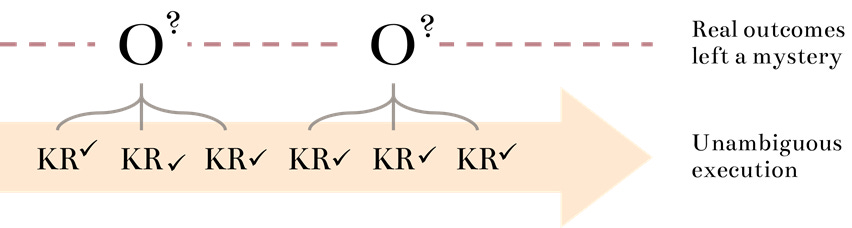

As Grove stresses in High Output Management, KRs must have a measure associated with them. Creating unambiguous outcome measures is challenging, however, and so people tend to focus on to-do lists instead. To-do lists are easy. But when this happens, the focus shifts to the proportion of KRs achieved (or, oddly, on the rated extent to which they are achieved).

With everyone’s attention firmly planted there, no one is really tracking whether the needles on these higher-level outcomes (the objectives) are being moved or not. Instead, we check the KRs off the giant, nested to-do list, and in the end, the whole exercise was a bit like reformatting a Gantt chart into a table.

2. OKRs might decrease your agility

As discussed by Grove, OKRs are meant to help teams pace themselves, prioritize work, and stay focused on what matters. The thinking is that while annual planning is costly and time-consuming, OKRs can (and ideally should) be set in a matter of hours. This can help establish boundaries around what specifically you are saying yes to. This is important since, as Grove puts it, every time you commit to something you forfeit the ability to do something else instead.

But remember, an OKR is a hypothesis—the KRs are the smaller outcomes the larger objectives are made up of. OKRs should be kept simple, fostering an ability to quickly assess whether they’re working out as hypotheses or whether they should be revised. This should happen as soon as the learning occurs. Often, however, OKRs become a behemoth nested structure revisited at some ridiculous set cadence (like quarterly).

Agile OKRs would be cool. We could call it “OKRA”. The problem is that if you’re learning your way to achieving target outcomes, as you should be, then just learn your way to target outcomes…all the extra baggage of an OKR structure isn’t even needed.

3. Surprise! They end up getting tied to your performance review anyway!

So, everybody knows that Rule No. 1 about OKRs is that they CANNOT be tied to performance reviews. Duh. After all, they’re supposed to be stretch goals. If you tied people’s performance reviews to them, then…. Yeah. Just call them slack goals. It’s Goodhart’s Law.

If everyone has to have individual OKRs—which is stupid—and you’re still doing performance reviews—which is stupid—then, well, stupid + stupid means something not very smart is going to happen. Just. Don’t. Do. It.

Deming was correct that performance reviews should be done away with. You wanna fix your culture and improve quality? Start by nixing performance reviews. So much ink has been spilt about Toyota Lean this and Toyota Quality that without ever once mentioning that another thing Toyota did was tell employees if you help us continuously improve, we will provide you with housing and guarantee your job for life.

So, let’s just say someone for some inane reason did tie OKRs to performance reviews. What would that even be called?

Let’s ask the product community.

Or here’s my friend Allen:

If at the end of the day, OKRs are imposed on you and tied to your performance review, what should you do? You probably can’t contact the CEO and get policy changed, but you can start where you are. How is your relationship with your manager? Start there. After all, for you, this is where the “rubber meets the road”.

If OKRs are tied to your performance review, what this looks like for you depends on the conversations you have with your manager. Are there some things you can do to educate your manager on OKRs? Has your manager read Christina Wodtke’s Radical Focus (probably the best book on OKRs)? Remember, OKRs are supposed to be about focus and continuous improvement. They are supposed to be about leveraging stretch goals as a catalyst for growth, which again only works if not tied to performance reviews. So, start there.

So, even if you can’t change your company’s policy, you can buffer yourself. Proactively engage with your manager about what YOU think tying OKRs to your performance should look like for you. If you’re not leveraging them to facilitate your career conversations, you should probably fix that first. Then keep them simple. As Andy Grove stressed, if you have too many, then you’re not focusing. Three objectives with three KRs each is already nine KRs. That should be about the max.

Until next time.

If you’re interested in coaching, contact me.

You can also visit my website for more information.