A common attitude about research is that it is a “nice-to-have”, or, even, merely “icing on the cake”. The assumption here is that research produces what are ultimately unnecessary refinements to the vital work that would already occur without said research.

Notice what is being telegraphed here. This statement is only true to the extent that whatever research is done will be ignored! (This is often the case, btw, as discussed here.) The very point of design research, however, is to determine what work the team should be doing in the first place. If discovery is “icing on the cake”, as the sentiment goes, then where did the cake come from?

When leadership reacts to discovery and agility as an affront to power, this shows they’re stuck in a bad frame. A better frame is that leaders are making bets and should want research to help them make smarter bets with less time and less cost. As Erika Hall has noted, if you were to ask an executive if they’d do some research before buying a $100K car, they’d probably say yes, right?

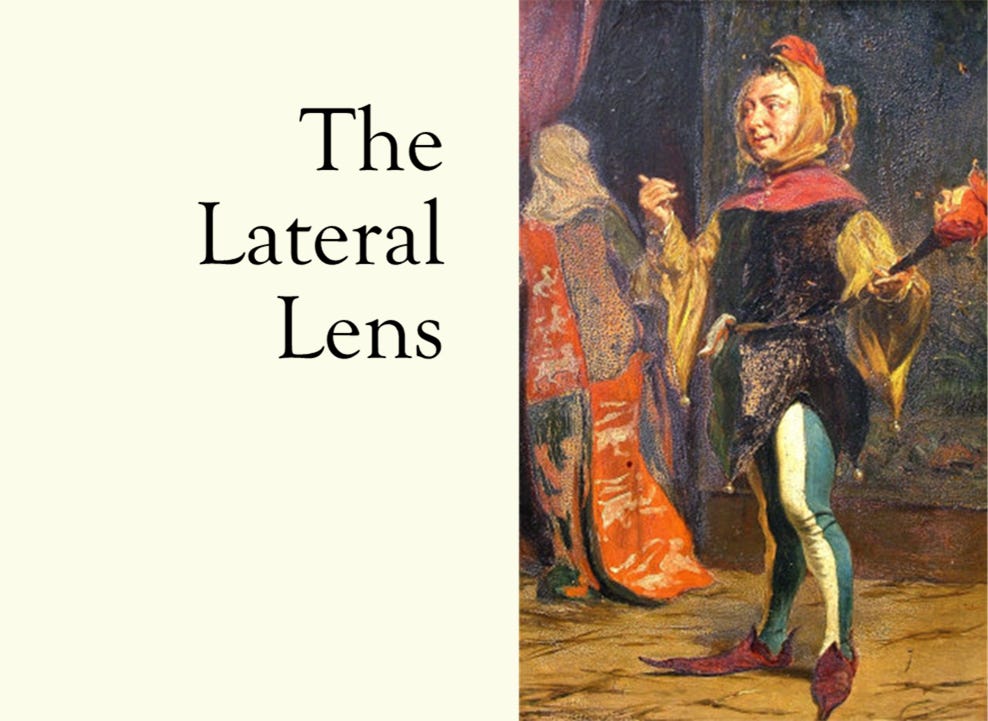

So why is it suddenly different when it isn’t their money? It shouldn’t be. This can be a powerful reframe. Consider the image below, adapted from Hias Wrba. Think of this in terms of Hall’s question. Whatever the idea is, how much of their own money would they be willing to bet on it? Would they bet their car on the idea? Their house? If they’d only bet a few days’ pay but the actual cost is more like a house, then they should probably want some research done first.

It can also be helpful to demonstrate how quickly you are in fact betting that much money. Here is a tactic I picked up from my friend Allen Holub. Say you want a Scrum team of 7 people to work on an idea for 2 weeks (10 working days). Ignoring the cost of delay of the idea itself, what is the traditional cost of putting 7 people on an idea for that long? Do you know? Do some investigating!

Let’s say the average “burden rate” where you work is $185K. Divide by average number of working days in a year (260), multiply by a load factor (x2) for computers, office space, IT support, HR, etc. Now multiply by team size.

OK, so…$185k ÷ 260 x 2 x 7 = $9962 per day x 10 days = about $100K!

So again, would you do some research if you were going to buy a $100K car?

Yes? Well, how is this different? If the idea could be derisked by even 15% by doing several hours or even a day of research, wouldn’t that be worth it? The answer should be an obvious yes. Do the math. Research that helps steer you toward value-adding outcomes is not icing on the cake—it’s better cake. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

For example, an Agile Manifesto coauthor once told me that, “You cannot deliver value if you’re not delivering working software!” I wholeheartedly disagree. The only way to create value is to change someone’s behavior in value-adding ways. Software is only one way to alter behavior. There are many others. The “working software” sentiment thus falls flat in two ways.

First, it is a mistake to confine yourself to that small of a box. Perhaps you do some research and learn that a workflow needs to be redesigned, a process needs to be improved, or a policy changed. The point here is if you’re trying to move a rock with a lever, software is not the rock—it’s but one of many possible levers. Conflating rocks and levers will only blind you to ways of increasing your overall leverage.

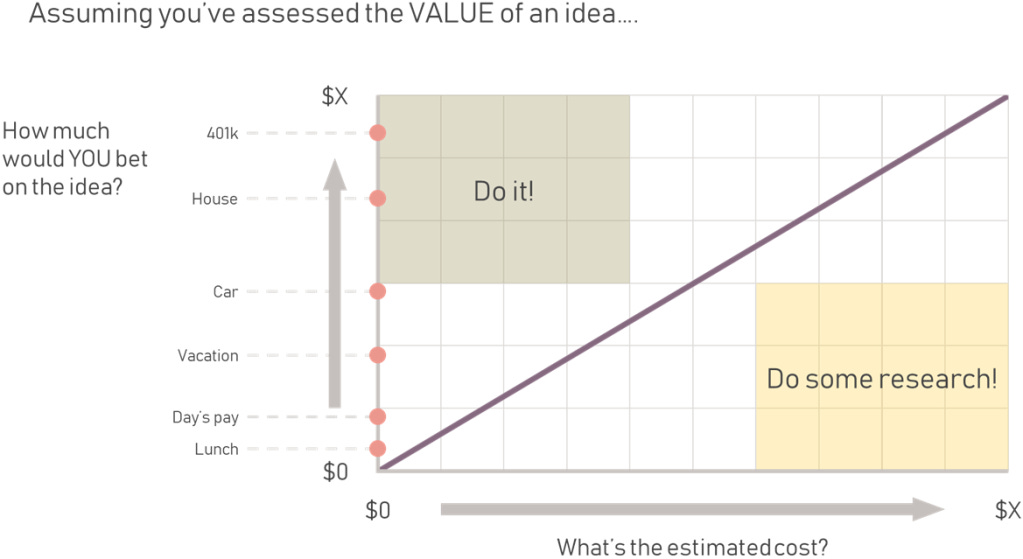

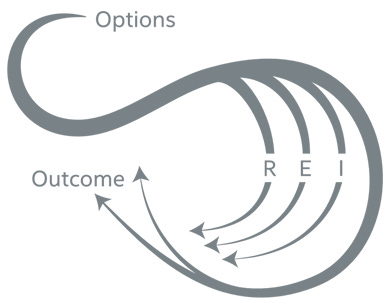

Second, this sentiment again ignores that research is cake and not icing; it oddly ignores the need for real agility in learning methods. If you do not need functioning software to debunk an idea, then taking the idea that far in the first place is an overinvestment. In other words, building faster than you can meaningfully learn is waste. Consider the image below, created by Gabrielle Benefield.

The desired user/customer/employee/etc. behavior changes you’re going after are outcomes. You explore alternative options for achieving desired outcomes, and iterate your way toward effecting these changes. In general, research (the R) is both cheaper and faster than running a full experiment (the E), both of which are both cheaper and faster than a full product increment (the I). In exploring options and learning your way toward outcomes, it should be considered a form of waste not to utilize all three loops as needed.

Let’s look at one more example. If a product increment tells you that an option is no longer a viable idea, great. But what if it took your team of 7 from above a month to discover this? That’s $200K. Say instead you had 2 people do some contextual inquiry with a few users. If you did 3 sessions, an hour each and 1 user per, that’s 3 sessions with 3 people each. Adjusting to an 8-hour workday, you can assume $185K ÷ 260 x 2 ÷ 8 x 3 x 3 = $1.6K.

The standard executive attitude might be that this is $1.6K of extra cost on top of the Agile team that would be working on something anyway…but that’s the wrong way to think about it. If that $1.6K of quick research led to a better idea, just as our $200K product increment did, then that is a $198K cost savings. And this is still just in terms of traditional cost. The actual savings would be more than this.

Taking a page from Stephen Devaux and his concept of Total Project Control, if both the quick research and the full product increment led to an idea that has greater value, then it likely also has a greater delay cost of not implementing it. Looking at the R, E, and I loops again, the loop that gets you to this idea faster also incurs less delay cost. This is important because, for truly value-adding ideas, the cost of delay will always far outstrip the traditional cost involved.

Now, an executive would probably rather lay someone off than smartly and quickly save that much money, but that’s another matter. A standard objection to the arguments here is that the money saved is not “real”. Again, this is an error. Think of it this way. Research that leads to pivots in direction is not “real” savings if and only if (iff) everything that would have been built is equally value-adding. This…typically isn’t the case. To the extent that some of what is built is waste, research that reduces this is in fact a massive cost savings, even if it is only derisking by a mere 5%!

To close, when teams fall into the mistake of treating research as a nice-to-have, there is often an assumption that needed research is happening in secret somewhere upstream...when typically, there is no such research. As Pavel Samsonov recently put it, programmers often talk about the “goalie problem” of being last in the waterfall, when the buck for research is passed indefinitely up the waterfall like a salmon looking to spawn. To twist the famous quote, in such cases there is no “evidence behind the curtain”. Its illusion all the way down.

Or, as Erika Hall has noted, if research is done, it is often meant to generate numbers to be used to help justify decisions already made. That’s not research—that’s marketing. Usually, the decisions made were not evidence-based at all. Instead, an idea was passionately advocated for in a meeting and then got funded, or was the pet project of some executive, the proverbial HiPPO (the highest-paid person’s opinion).

Passion is great, but we need to create a space for actual derisking.

That’s how you maximize value.

Until next time.

If you’re interested in coaching, contact me.

You can also visit my website for more information.