Starting With Value

In Total Project Control, Professor Stephen Devaux contends the purpose of a project is not to be short or inexpensive, but to create value. One might think this was uncontroversial. The way most orgs approach project work, however, one wonders.

Prioritization is like a mirror. The way it is approached reflects an organization’s true priorities, which are often not what it claims. Organizations typically focus on delivery, delivery, delivery; and yet, without a focus on how decisions made then impact resulting user behavior and, ultimately, project and product value, why would delivery matter?

I increasingly see people argue that since value and delay cost “cannot be known up front” that they should not be focused on at all. This is a dodge. As Devaux points out, the value estimates are already there…whether you realize it or not. The pertinent question is whether they are visible. Ignoring this tosses the focus back on cost and duration while overlooking what matters most. In general, then, it is better to ignore those arguing that value “cannot be known upfront” and instead make assumptions visible.

After all, your definition of value matters more than your definition of done. So define it. Surface and itemize the assumptions at play. As Devaux advises, this should begin with value estimates of the benefits you want to achieve (objectives and outcomes) before then moving to what you think will achieve them (output). In Managing Projects as Investments, Devaux offers a helpful rubric for tying objectives to value drivers. For both products and projects this helps you begin with the end in mind, which helps identify risks and makes prioritization easier.

Value drivers should frankly be the main focus anyway. Without value-generating outcomes and objectives the ROI of all output is negative. Thus, whatever scope ideas occur at the output level should be tied to prioritized outcomes. This is often difficult though when starting with output. Beginning with the end in mind also makes this easier. As Gojko Adzic notes in Impact Mapping, it is far easier to come up with target outcomes by reverse engineering them.

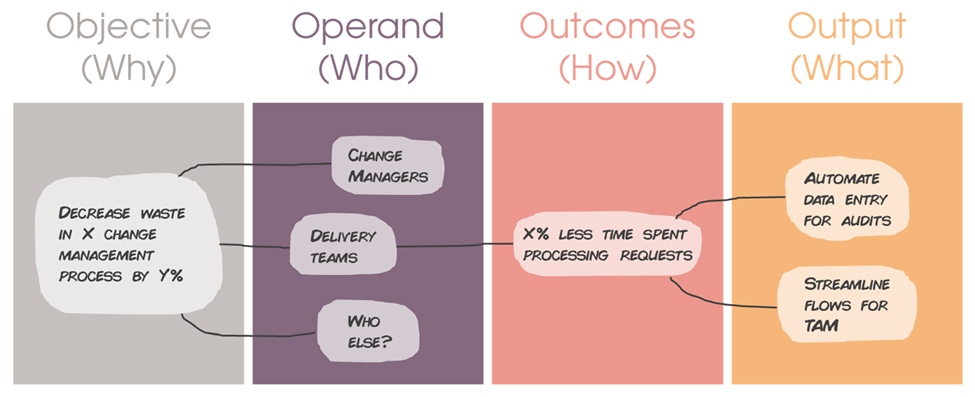

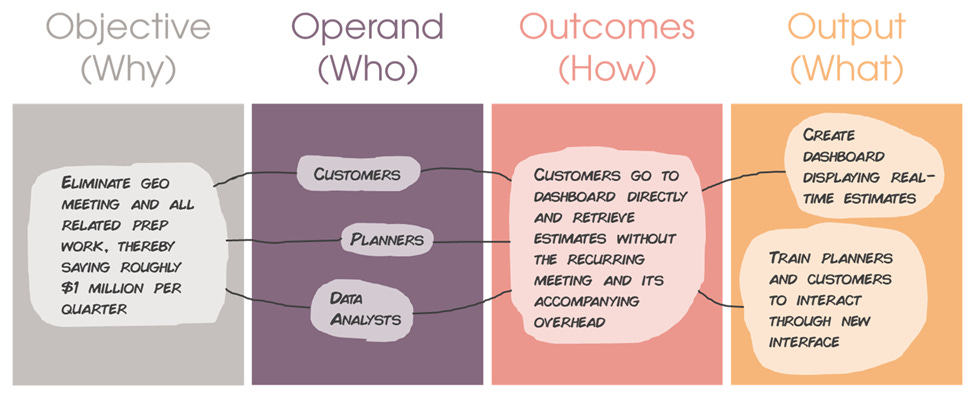

Start with an objective, a business goal, tied to a value driver. How would the world need to be different to achieve this goal? (That’s an outcome.) Whose behavior would need to change? (They’re the operand.) How can you meet their needs and create value for them in a way that will also elicit the desired change? (That’s your output.) Ideate and prioritize. Map it out, as shown below. Get the right people together and facilitate them through this structure.

You will likely be me with resistance. That’s fine. And yes, it can be scary. People are afraid of being “wrong”. But here’s the thing, the aim isn’t to be “right” as much as it is to frame explicit hypotheses up front that surface the assumptions at play so they can be challenged by all involved. If you start learning your way forward and you need to rethink the logic, then do it! At least you are now learning your way toward concrete goals instead of focusing on output theatrics.

By mapping this out with the right group of people, you are enabling a diverse group of subject matter experts to weigh in, up front, before any cement has been poured. Those who argue against such practices because, again, value “cannot be known up front”, are essentially claiming a decision frame cannot be optimized if you don’t have a crystal ball. This is an odd position that frankly goes against the entire field of Decision Quality.

If you do not have established objectives, such as from an existing OKR process, then start by having the group freelist problems they are facing related to a big, expensive issue. (As Nick Disabato asks, if it’s not an expensive issue, then why are you going after it?) Have participants write down pain points, obstacles, and general thorns in their sides, one issue per sticky note (whether physical or virtual doesn’t matter). As Erika Hall advises in Just Enough Research, don’t make this into rocket science. It’s meant to be a quick and informal exercise to help the group surface and synthesize its collective knowledge.

This process should also largely be silent. You want participants individually recording their thoughts as opposed to verbally brainstorming. When finished, read the comments out loud, discuss anything unclear, and then have the group cluster like sticky notes together. Don’t overthink the groupings. (Again, this isn’t rocket science!) Discuss and label the emerging themes for each cluster. Explore themes for candidate objectives. If you have more than several, then have the group rank them, discussing how they relate to the value drivers above.

Ideally, what is happening here is that a diverse group of experts close to a problem have collectively generated and clustered related issues, surfaced larger-scale themes, and explored them to prioritize the best opportunities to go after. From here they can choose an objective and then build the rest of the map. Who are the operands at play? How would they need to change (outcomes) to move toward (or achieve) the objective? What work (output) would meet their needs in ways that will generate these outcomes?

Many objectives and outcomes should have specified targets. Choosing these can be challenging. To make it easier, as Christina Wodtke advises, separate the discussion into two smaller decisions. First have the group decide on a measure and a direction. As in the example above, you can insert a placeholder for now, such as, “X% decrease in time spent processing requests”. In a later meeting you can have the group debate what the target value should be, such as “20% decrease in time spent processing requests.”

Yes, this approach to planning might seem like added work—of course it does. It calls bullshit on output theater and requires teams to strategically think things through. The pushback to this should be overcome. At the end of the day, the “successful” delivery of obsolete guesses is simply a failure to adapt and improve. And the longer this goes on, the greater the opportunity cost.

In his work, Devaux interestingly refers to this as the “planning paradox”. As he puts it, people tend to think that if they had a crystal ball, then they could write the “perfect plan”. This, he contends, stems from a misunderstanding of the very purpose of planning. The reality is the more you can really predict the future the less that planning even matters. The real point of a plan is not to predict the future but to organize resources so that you can do big things in the face of uncertainty.

Agilists sometimes argue that planning ahead is wasteful. Obviously not all planning is waste, else there could be no strategy. What they mean is that spending time up front elaborating output often ends up being waste. This is true. If assumptions change as you work, then you need an iterative approach where better information emerges from the process of engaging with the context at play. This gets us back to what Devaux argues is the purpose of planning, which is to provide organizations with both structure and flexibility.

The approach outlined here helps you both plan and travel light. This helps you scale and flexibly ensures agility. This adheres to the spirit of Devaux’s arguments while diverging on some particulars. Here, for example, you probably will not be building out a detailed work breakdown structure outside of the context of the first bet made. Here, value is instead tied to the level of outcomes and the focus is more the delay cost of not achieving them. Shifting expected monetary value (EMV) to outcomes, however, still allows for much of Devaux’s approach, as output is then framed as bets with an estimated time and cost to realize the EMV of specific outcomes.

The benefits hopefully are clear. Mapping this out helps teams think more strategically. Aligning on a target outcome opens up a space to then explore multiple alternative ways to achieve or advance it. This allows for easier ideation and lateral thinking, enabling more of a cumulative as opposed to the standard linear approach to strategy. This also gives teams a clear “Why”, thereby increasing buy-in and leveraging their greater situational awareness to discover better paths forward.

Until next time.