Intro

In today’s Lateral Lens you will learn how to create and use influence maps to increase your impact and achieve better outcomes. As executive coach Tom Henschel notes, the entire notion of “political savvy” seems off-putting to many people. If this is true for you, you might want to dig into why you think this. This is, after all, a lens that you are bringing to the table; and, furthermore, it is a lens that is likely damaging your career.

It needn’t be this way.

Thanks for reading The Lateral Lens! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Subscribed

Yes, there are corporate cultures where Machiavellian scheming is more the norm than others. This is a separate from the simple fact that you will achieve better outcomes in the long run if you learn to up your influence game.

Henschel suggests this reframe to his clients. If you tend to think, “I hate politics”, would you equally say, “I hate relationships?” After all, politics can be both positive and self-empowering. As Henschel puts it, whenever you act in the interest of your own future success, you are being political. This acknowledges that we are social creatures and that achieving big things requires skills akin to community organizing.

If this changes how you feel about political savvy, then it will also change how others experience you as you network and influence. Political savvy is necessary because, sad but true, good work does not speak for itself. And just as work does not speak for itself, neither do data. Influence in general is not a matter of “making your case”.

If your sole focus is crafting the “perfect argument”, then, again, you are back in the trap of assuming your work will speak for itself. The fact is that facts do not influence, rational arguments do not influence—influence influences. Ignoring this can be called the “Sir Galahad Fallacy”, which is to assume that others will be influenced by your argument if you just make your case well enough.

Paraphrasing Byron Katie, information is not conveyed as much as it is interpreted and weighted, filtered through a prism of social (indeed, almost tribal) dynamics. Trying to influence while ignoring such dynamics is a fool’s errand. No matter how much you think you have the “facts” on your side, influence is a different game.

Ok. In this article you will learn a technique that can greatly increase your ability to influence. The concept is similar to the Japanese idea of nemawashi, which means “working around the roots”. This refers to the informal influence that lays the groundwork for a decision prior to any formal discussion.

Influence mapping (a.k.a., power mapping) comes from the world of community organizing. There are a variety of flavors out there. I originally learned a variant from Joel DeLuca’s excellent book, Political Savvy, which I then altered by pulling in additional ideas.

Let’s get started.

Creating Your Map

Influence has to do with stories, relationships, and how information is emotionally tagged. People digest information in different ways, depending on their history, assumptions, and values. People also have egos and self-esteem needs. They care about image and status. They often will not support a decision if they do not feel their position has been heard and taken into account. Influence, then, is ultimately about relationship building. Its best medium is conversation.

An influence map is made relative to some decision, something you want to have changed. Whatever the target decision is, who has the authority to make it? Is it an individual? A group? This decider, the “D”, is the person or group you are ultimately trying to sway. If you do not know who this is, schedule some meetings and find out. The first step in creating an influence map is to list the key players. Whether doing this alone or with a small group, use the listing questions below to help identify them.

When listing, cast a wide net. It is better to identify more people than necessary than to leave important players out of the picture. Influence is a team sport. We are so used to functioning as teams for so much of our work that it’s a bit surprising we so often try to influence alone. Listing key players will help you model the decision environment at play, the context the D is operating within. Working your map will then help you evolve the decision landscape to your advantage.

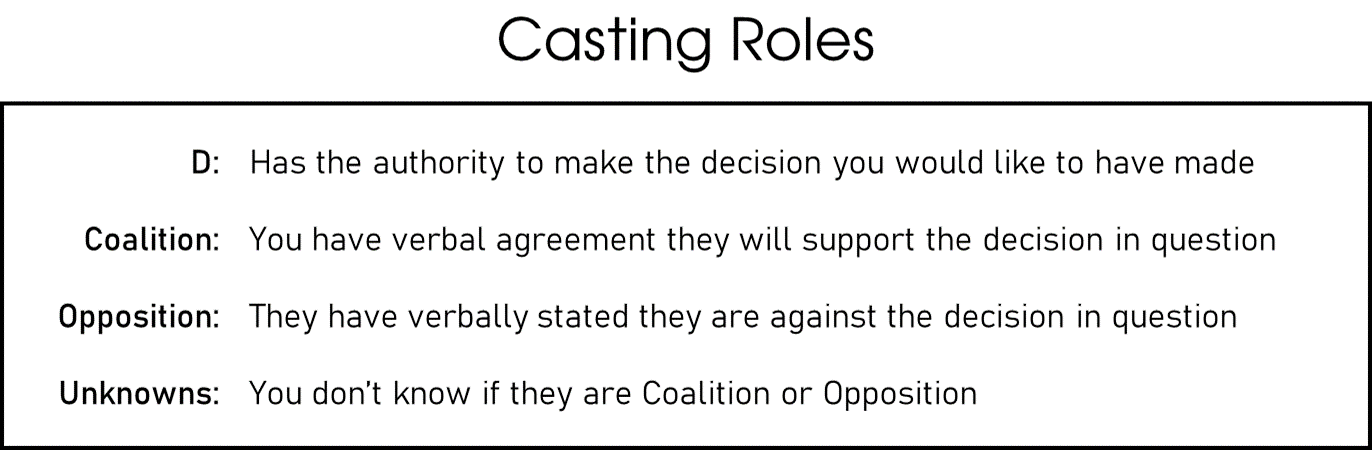

The next step is to “cast” the key players you’ve identified. In addition to the D, you will now cast stakeholders as being either Coalition, Opposition, Coplayers, or Unknown. You may not know everyone’s role at this point, and that’s fine. It’s still important to just fill in what you think is the case. This information might change as you work your map—that just means you’re learning. For now, most people might even be Unknowns. That’s also fine. The meetings you will soon be having will iterate your map, filling in more data as you go.

As you work your map you will be building a coalition of support around the decision you would like to have made. When you find out who the D is, try to learn how they tend to make decisions. Whom do they tend to listen to? Who has the D’s ear? Who is on the D’s team? Whom do you know who knows them? Think of this as network building.

Who do you already have a verbal commitment from that they support the decision in question? These people are Coalition. Anyone who has said they are against the decision are Opposition. Coplayers are anyone who might feel like you are stepping on their toes, people who might already feel like they “own” this issue. If you do not align with them, gain their blessing, and pull them in, they might try to thwart your efforts.

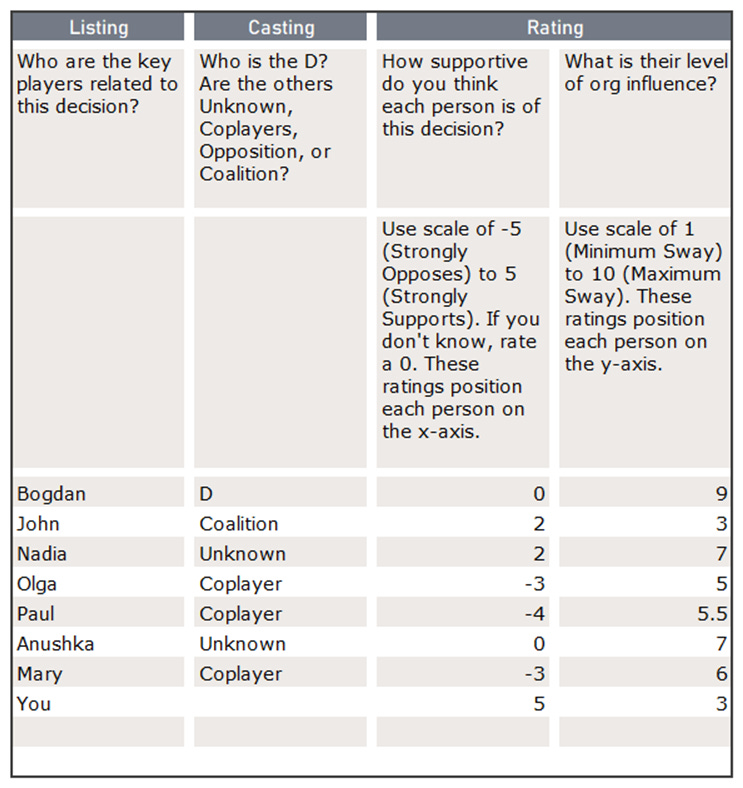

After you’ve done a first pass at casting, next you will rate key players on two variables. The first is their level of support for the decision in question. This is your best guess, based on your current gut feeling. Second is their level of org influence, also your best guess.

Go ahead and include yourself in this. Some approaches to influence mapping place “You” at the center of the map. Not this one. Go ahead and rate yourself. Hopefully you are in favor of the decision you would like to have made 😊. Your level of org influence, however, is likely lower than the D (or you probably would not be doing this). Together this means you will typically be on the lower righthand side of the map. The scales to use are explained in the spreadsheet shown below.

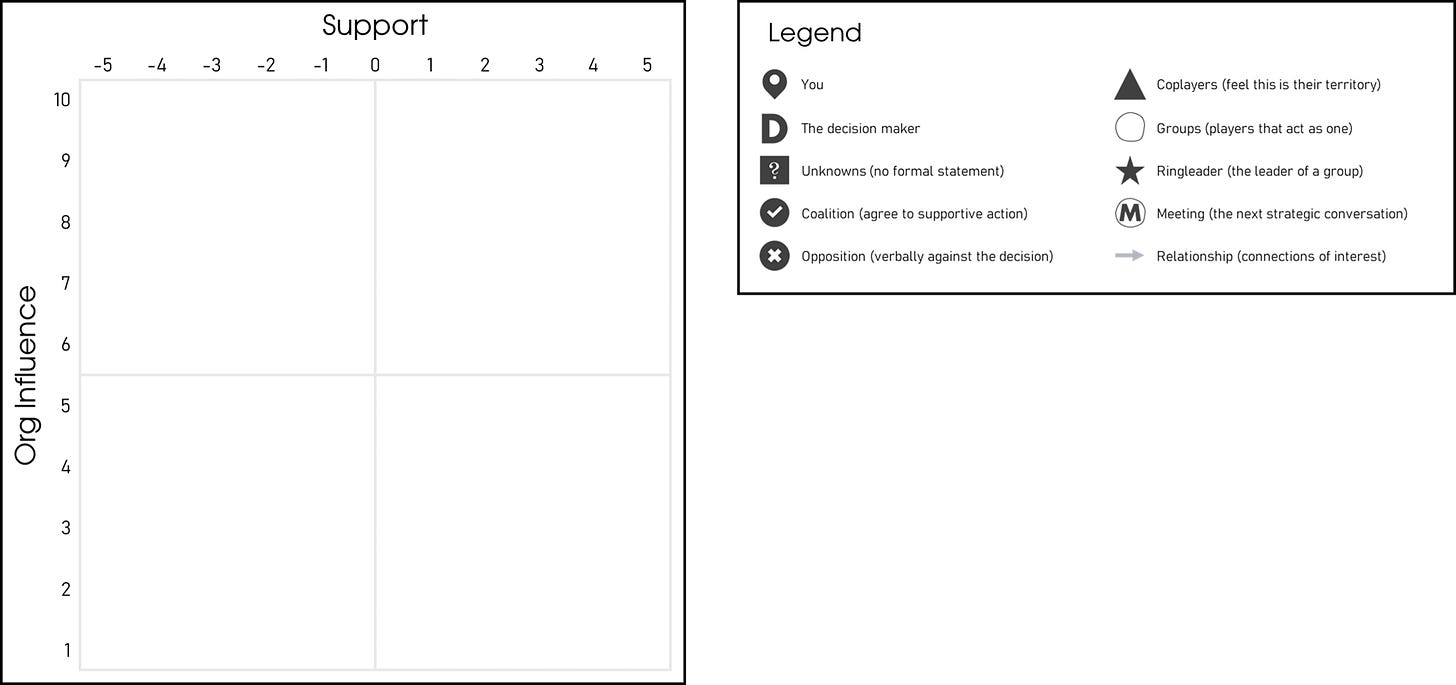

Once you’ve done your listing, casting, and rating, put everyone on the map. Below is the grid and a Legend of symbols. If you would like a copy of the templates shown here, complete with the icons ready to be dragged and dropped for the mapping, feel free to email me at charles.lambdin@gmail.com.

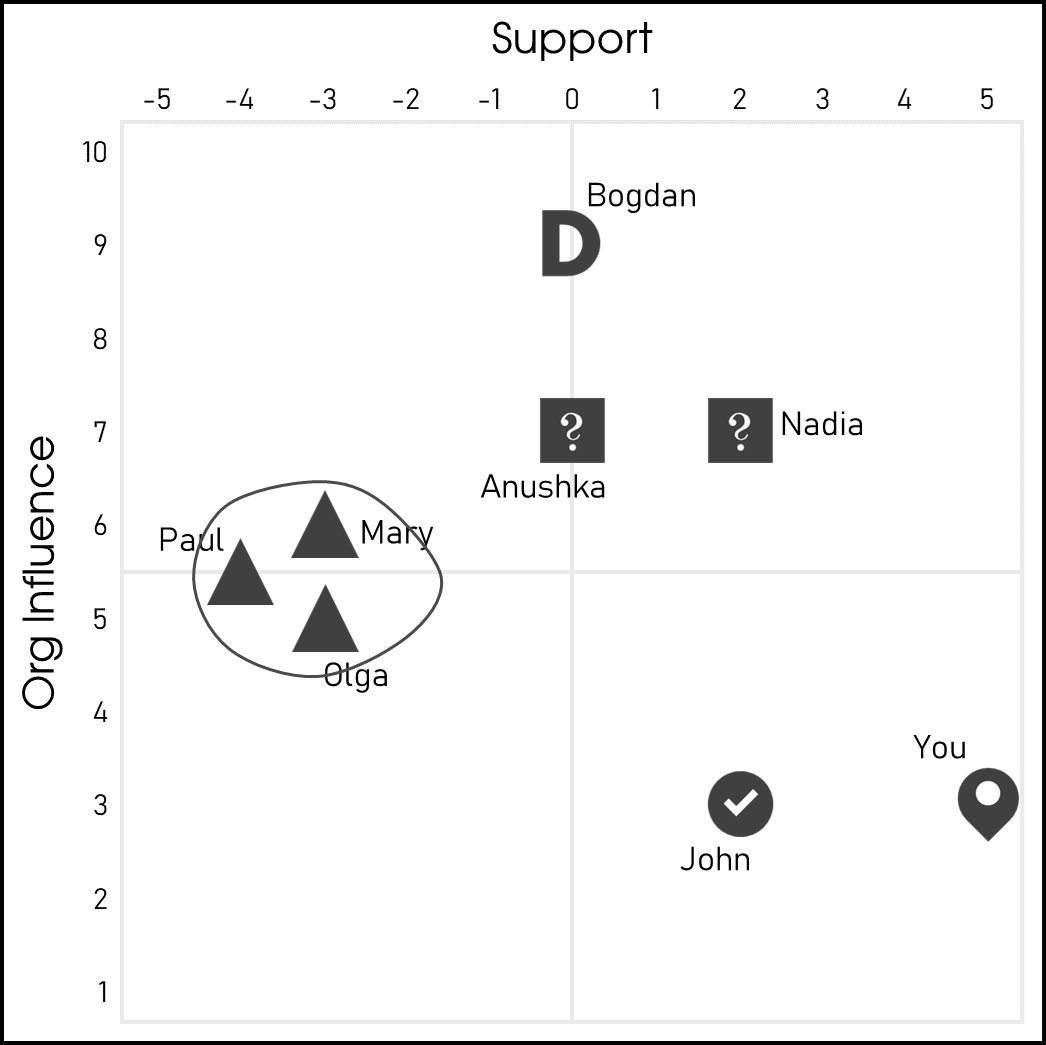

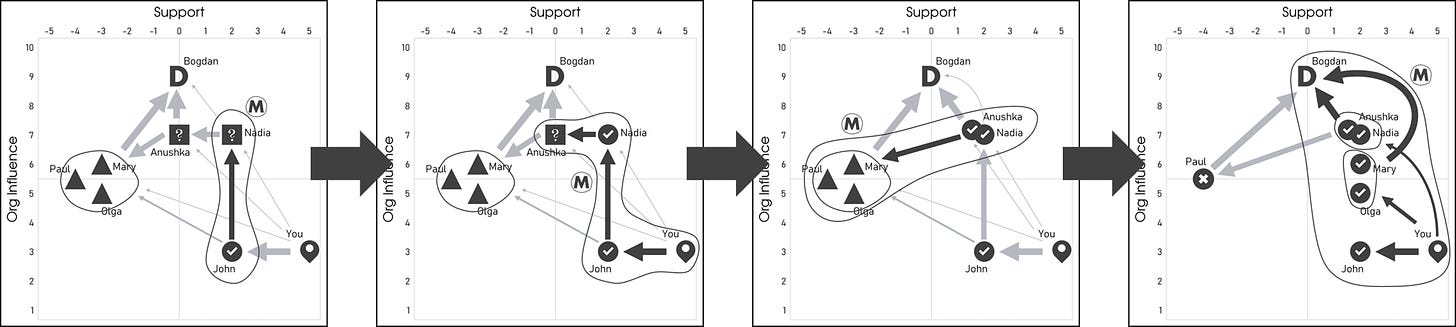

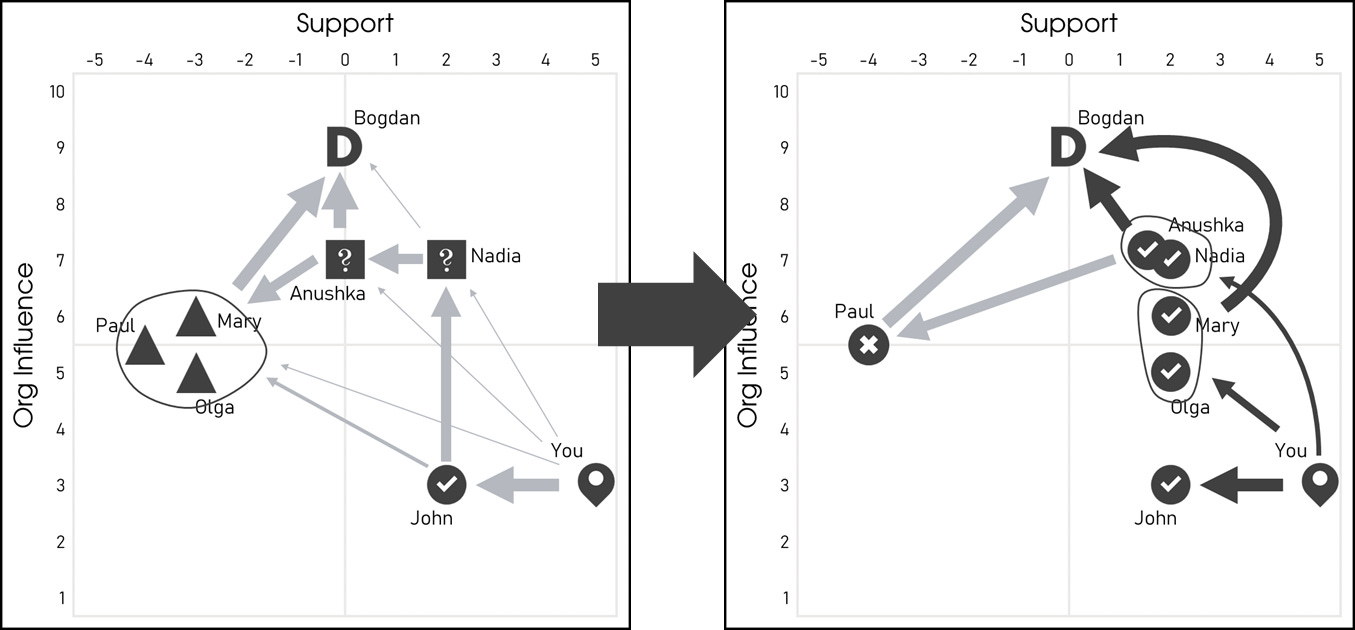

Use your ratings to position each stakeholder on the matrix. The level of support is plotted on the x-axis. Level of org influence is on the y-axis. In the present example we have the D, one Coalition, two Unknowns, three Coplayers, and You. Using the casting and ratings depicted in the spreadsheet above, the initial map would look like the image below.

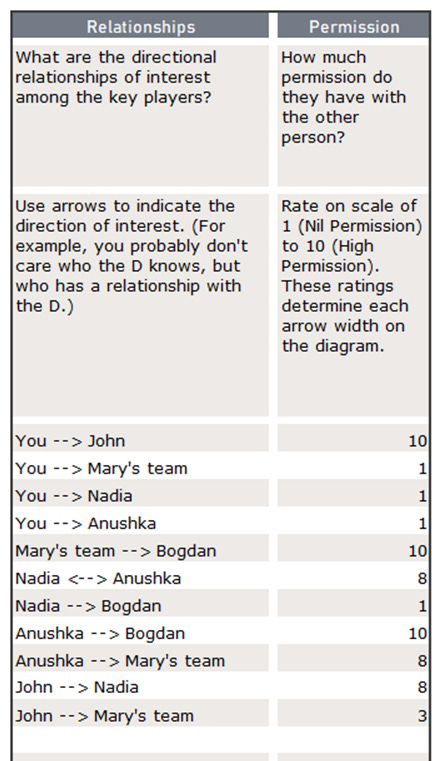

It’s now time to add relationships of interest. In the spreadsheet, indicate with directional arrows who has influence with whom. Next rate the “permission” of each relationship, a concept I learned from Michael Grinder. Permission is one person’s level of receptivity to another’s influence. This not the same thing as rapport. You might have good rapport with someone who is still not open to hearing from you on a particular topic. Thus, while establishing rapport can make a difference, it’s not sufficient to influence. (In fact, it’s not always necessary either.)

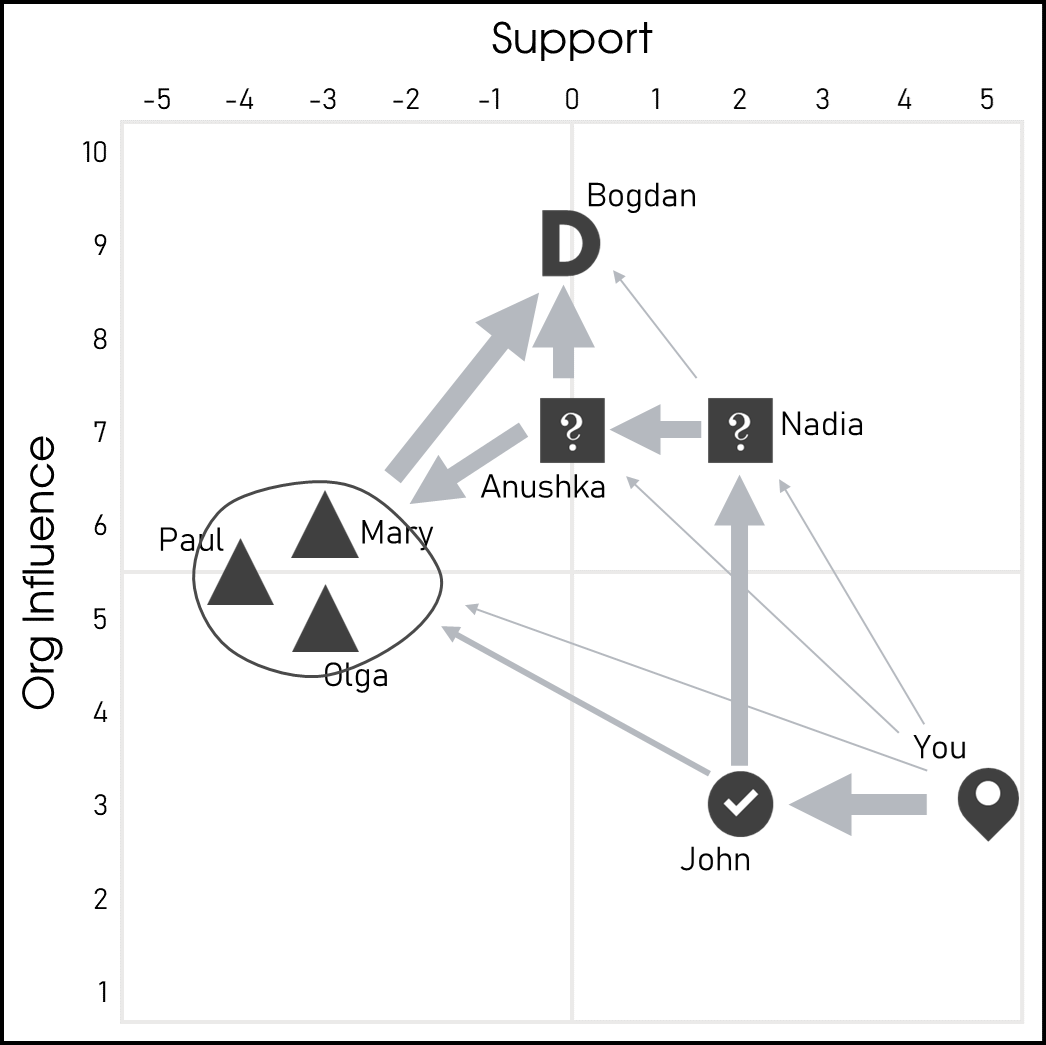

When added to the map, the arrows build out the possible influence paths from you to the D. Your permission ratings are represented by the thickness of the relationship arrow. If using PowerPoint, each rating becomes the literal width of that line. For example, a relationship with a permission rating of 7 is now a line with a width of 7 pts. (Neat, huh?) Adding this new data, you now have a complete influence map:

Just glancing at this, a few things are suggested that may have not been readily apparent before.

Using Your Map

Creating the map required you to think about and visualize the social dynamics around the target decision. Now you will use your map to evolve the landscape in support of the decision you would like to have made. While proceeding, do not assume that people marked Opposition cannot still be of help. They will often still give you advice or tell you who you might talk to next.

Similarly, people you have marked Coalition can still get in your way. Borrowing a term from Alan Weiss, some might be “gatekeepers”, people who pledge their support while simultaneously blocking your access to the D. Sometimes gatekeepers are legitimate and then become the D by proxy. Sometimes they are more trying to protect their own status, in which case you might need to network around them, making them in effect Opposition.

Start by looking for wide “permission paths” that help get you closer to the D. In the map above, for instance, there are only two high-permission paths to Bogdan. One is Anushka. The other is the group of Mary, Paul, and Olga. They, you believe, also tend to listen to Anushka, forming a triangle. You yourself do not have high permission with any of them. Nadia does, however, and she also tends to listen to John, whom you already know is in favor of the decision you would like to have made.

This suggests the first step of having John meet with Nadia on your behalf. If John is successful with Nadia, then you could have her meet with Anushka. You could also have Nadia introduce you and John to Anushka and then set up a meeting with the four of you. Ultimately, you should do whichever you think is most likely to produce the desired outcome. Nadia may have a better sense of which might go over better and so should be involved in planning the next step.

Let’s say all four of you meet and Anushka is also on board with the decision. You then send her and Nadia to meet with Mary, Paul, and Olga. Mary and Olga say they will support the decision in question, enabling you to set up a meeting with Bogdan, Anushka, Nadia, Mary, and Olga. This leverages their combined wide permission paths to the D.

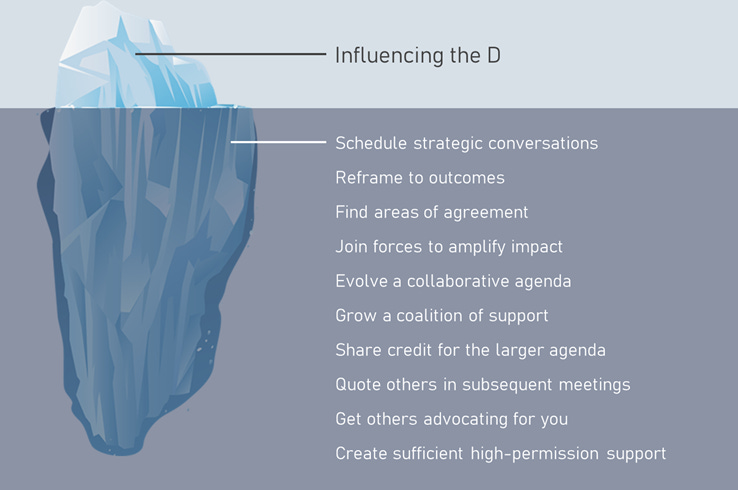

Notice how different this is from what we usually do. If you’re like me, normally you would get on the D’s calendar and spend your time crafting the “perfect presentation”. This brings us back to Henschel’s point that influence isn’t about making your case. It also ignores, as DeLuca points out, that higher-ups often have their own “mini-culture” around presentations. Often ideas are praised just to signal moving on from them and you never learn what people really thought. Agreeing to present in this way poses a similar risk to consultants agreeing to pitch—you’re already giving much of your influence away!

Instead, focus on nemawashi, on informally setting the stage for success. Broker the right conversations to iterate the map. Since meetings are largely the medium of influence, it pays to be strategic about them. The effect of any series of meetings in part depends on their sequencing. Every meeting you hold adds new information, corrects where assumptions might have been off, and indicates logical next steps. This both alters the map and creates new options. In the present example, for instance, just look at how different the map looks after only four strategic meetings!

Until next time.

If you’re interested in coaching, contact me.

You can also visit my website for more information.