Intro

Marxism might seem (to some) an odd lens for product work. There are, however, many concepts from Marxism that are extremely helpful for examining aspects of both product strategy and organizational leadership. For instance, I have long thought there are characteristics of both Agile and Design that are highly similar to Marxist approaches.

If this sounds nuts, well, I invite you to read with an open mind. You might be surprised. In this post, we will focus on the Marxist concept of base and superstructure, the Leninist concepts of commandism and tailism, the Marxist notions of struggle and contradiction, and, finally, the Maoist concept of the mass line.

Let’s get started.

Base and Superstructure

Marxism rejects “Great Man Theory”, which sees history as driven primarily by the actions of “great” individuals. Marx’s approach, historical materialism, along with its Hegelian dialectics, can be thought of as a precursor to modern dynamic systems theory. Here, important innovations, inventions, and reforms do not primarily stem from the actions of individuals as much as emerge from larger systems and, as we will see, their inherent contradictions (or conflicts).

Here, ideas, like technologies, are the result of a process of evolution. As such, all knowledge is collective. Our insistence that history is a story about various personalities is, in this view, an ad hoc narrative fallacy. Take the theory of evolution itself: Darwin didn’t “discover” it as much as we today discount the larger fabric from which it emerged, emphasizing in retrospect the role his writings played in the paradigm shift that followed. Similarly, no one “invented” the computer or the car or the lightbulb—they are ideas that evolved across both time and people.

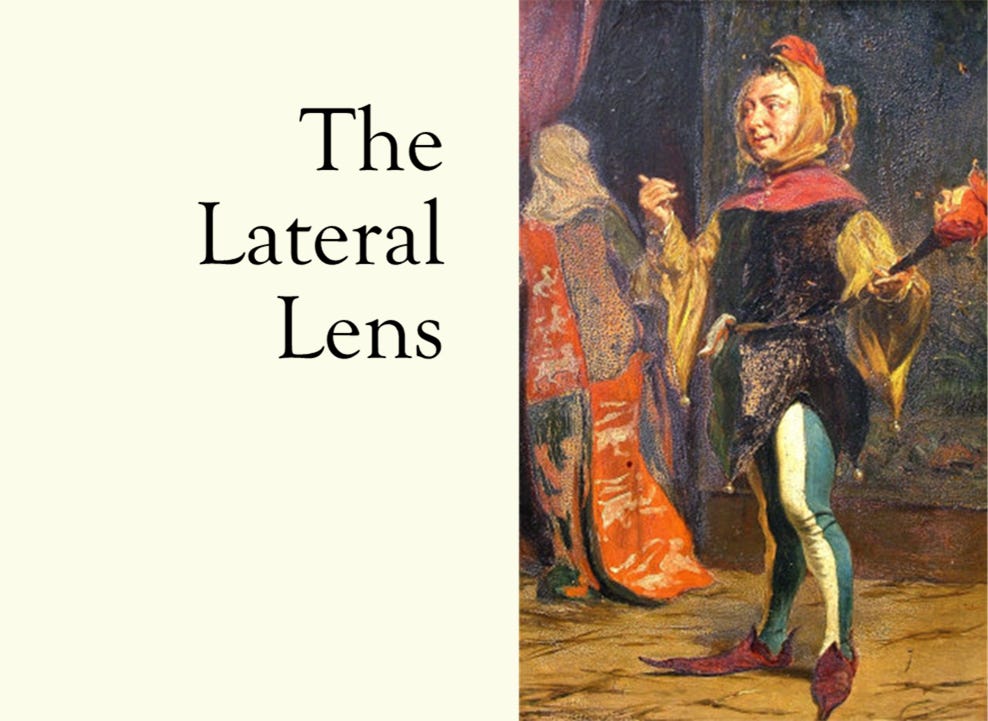

In rejecting Great Man Theory, the aim is to zoom out from individuals to the larger systems at play. As Marxist economist David Harvey has put it, to blame outcomes on individuals distracts from system’s responsibility for producing the effects that it does in fact produce. This likely sounds familiar. To quote Deming, “Every system is perfectly designed to get the result it gets.” Such thinking permeates Marx’s notion of “base and superstructure”. The results we get are often “superstructure” stemming, at least in part, from some underlying systemic or economic “base”.

We love focusing on superstructure. Keeping the story about personalities not only sells the news but also serves to distract from the actual system at play. Once you realize this you begin to see that the base itself often operates outside our frame. This is true even in a corporate setting: We announce a new corporate culture with new values. We roll out a new policy. We give management new training. We ignore that this is all superstructure and the most effective way to change an organization would be to alter some aspect of the underlying base.

This can be thought of as organizational root cause analysis. The point is to stop intervening at the level of symptoms. Superstructure changes not reflected in the base are often just lip service. So, instead of telling people what their new values are, give them better tools, give them better resources, and/or change how they relate to their customers. Instead of announcing a “culture of innovation”, change what behaviors are actually being incentivized.

Commandism and Tailism

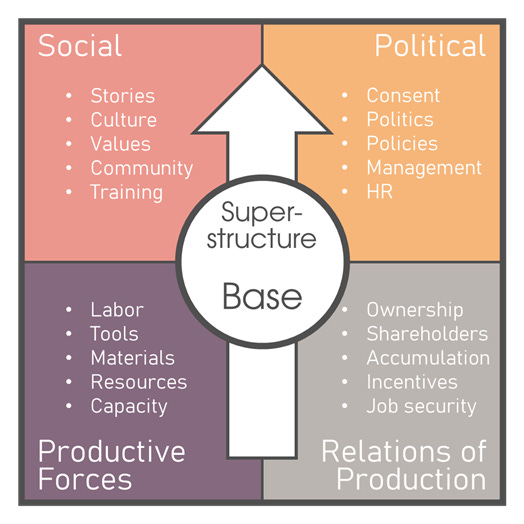

Commandism is when leaders use formal authority to push an agenda against the will of those they lead. This is a failure to surface solutions from social investigation that the masses themselves accept. Lenin contrasted this with tailism (khvostism), which is a wholesale failure to lead. Whereas commandism is to dictate, tailism is to follow, making it akin to populism. Both fail to optimize results for the group, commandism by abandoning the principles of cooperative action and tailism by not surfacing better solutions than whatever people happen to ask for in a given moment.

In most organizations we tend to do research only after we have a predetermined focus handed to us, such as a product that has already been decided on. This is commandism, ignoring that whatever we happen to think users are struggling with is not a substitute for engaging with them and surfacing larger systemic issues. Conversely, if we confuse design research with taking requests, that is tailism. This fails to root cause and surface bigger issues. It also fails to work with, reframe, and improve the assumptions of the people we are engaging with.

Struggle and Contradiction

As Deming once said, “A system cannot understand itself.” It’s like McLuhan’s fish. “Struggling” is how we learn about the water we are in. Instead of seeking individual opportunistic gains within the system’s status quo (what Lenin criticized as “opportunism”), we strive to keep the focus on the continuous improvement of the system itself. This requires consciousness raising and the exposing of the base at play. Whatever the issue in question, we should link it to the system by identifying underlying political issues and, in a Hegelian sense, by seeking the principal contradiction or conflict determining results.

Consider Donella Meadows’ notion of “dancing with systems”. As she puts it, we must engage with systems in a way that surfaces mental models and exposes them to the air. This is essentially what organizers mean by “struggle”. Struggling exposes the system and brings it into view so we can then focus on improving it by identifying and working with its inherent contradictions. This is the process of dialectics. Every system contains opposing forces or “contradictions”.

As Marxist activist Torkil Lauesen notes, identifying the principal contradictions at play allows us to discover more optimal ways to then intervene in (or struggle with) the system, which then improves our analysis. Logician Kelvyn Youngman has compared this to Goldratt’s Evaporating Clouds. As Youngman observes, Goldratt’s cloud diagrams are not causal as much as they are dialectical, focusing as such on the resolution of opposing forces (i.e., contradictions).

In Marxism proper this process tends to focus on contradictions related to ownership and economics, such as corporations emphasizing free market capitalism externally while internally operating as planned economies, or that the web of work that makes corporations possible is already socialized and largely unremunerated, depending as it does on the social reproduction of people, education, and skills, whereas the ownership of said corporations is private, which is then viewed as a transfer of wealth from the many to the few.

The Mass Line

Mass systemic work requires mass struggle, which requires mass organizing. The mass line is a philosophy that enables this. It can be compared to a centralized factory focused on the production of improved systemic understanding. This is related to Lenin’s argument that grassroots organizing should be aided by a central vanguard organization operating in a parallel, tops-down fashion. It thus emphasizes the importance of centrally surfaced strategic objectives enacted through decentralized tactics, a key similarity to the older Austrian military doctrine of Auftragstaktik.

In the mass line, we draw upon the experience of the group we are aiding as our main source of information in organizing to then improve their conditions. This begins with an analysis of the group and its larger context. We immerse ourselves in the group and learn about their needs and problems. We refine our analysis as we go, iteratively improving our understanding of the system. In this way, the Marxist process of cyclic theory and praxis (practice) is not all that unlike what is now described as “agile”, or Lean Startup’s concept of “build, measure, learn”, or design’s older notion of “design and critique”.

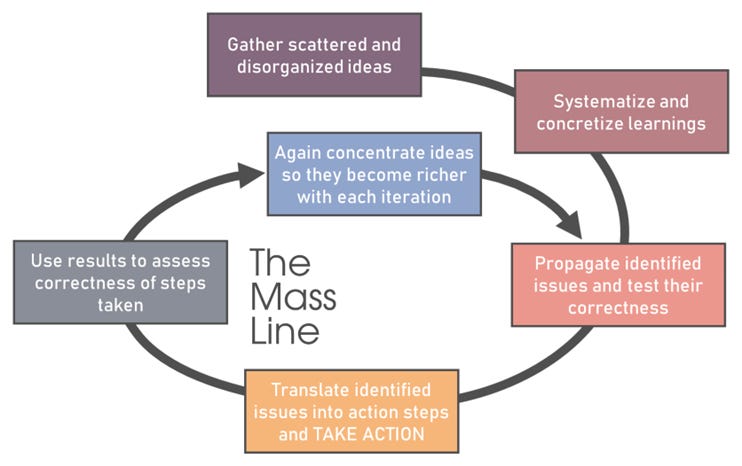

This process is described as a spiral wherein we learn, synthesize, share our summations back with the group, and assess whether they resonate. As we proceed, we consolidate gains and continually improve our approach. As we reengage with the group, they internalize discoveries that resonate as we then collectively decide on actions, building a network as we simultaneously amplify impact. According to this philosophy, it is this engaging with and immersion in the masses that grants leaders legitimate authority. The spiral below visualizes the overall process, as described by Mao in “Some Questions Concerning Methods of Leadership”.

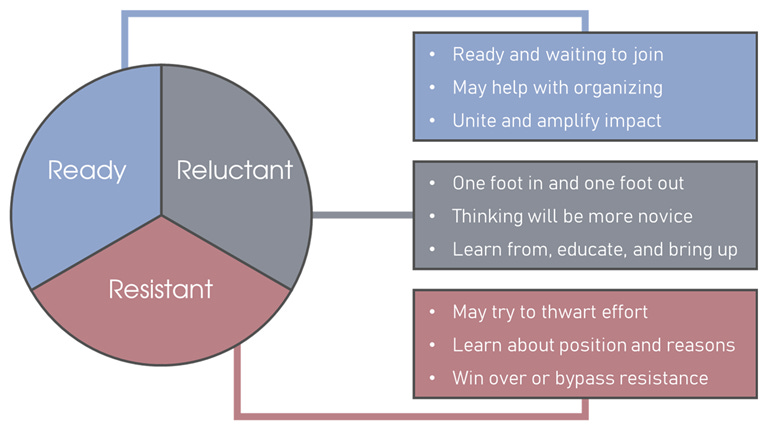

A crucial concept in this process of joint discovery and organizing is the use of segmentation to customize the overall approach. The mass line stresses the importance of distinguishing between the advanced, the intermediate, and the backwards (or reactionary), or as sometimes stated, the active, the semi-active, and the inactive. We will here use the terms the “ready”, the “reluctant”, and the “resistant”.

To maximize impact, we should seek to identify, unite, and leverage the ready, learn from, motivate, and mobilize the reluctant, and either educate and win over or bypass the resistant. We must remain flexible in this, as conditions are always changing. All efforts have their own lifecycle, and people who are ready at one point will be reluctant or even resistant at others.

Relevant here is Deming’s concept of critical mass and the square root. To effect change, start with the square root of the size of the organization. In a company of 100K, that is about 300 people. Do not spend too much time trying to persuade detractors. Focus on growing a coalition and then leveraging their networks to further expand it.

As we network, learn, and educate, it is important that we also increase the skills of everyone we work with so they can themselves adopt this empirical and iterative approach. This will not only amplify impact in this particular effort but will then enable them to launch their own efforts in the future, which is in the long run more important than any isolated gains. This helps build the organizational muscle of keeping the focus on the larger system and striving for its continuous improvement for all involved and not just the few in power positions.

Conclusion

To close, these concepts, stripped of emotional loading, are useful in many contexts. One could argue they are largely political, but, then again, all org change work is essentially political. Design, furthermore, is at its core the optimization of decisions within given constraints to achieve certain outcomes, which itself entails conflict, politics, and organizing.

To ignore this is to limit our impact and potential.

Fun, if a little brain bending