Influence Mapping (Part 2)

This is Part 2 in a three-part series on influence mapping. In Part 1 we went over how to create the map. In this post we will cover how to work the map to evolve the landscape. In Part 3 we will look at some more examples and summarize the principles covered in this series. If you have not read Part 1, go here first.

Intro

In the late 1970s President Ford sought to thwart rising USSR and Cuban influence in Southern Africa. Cuba was pouring troops into the area surrounding Rhodesia, a white minority rule country Ian Smith had declared independent of British rule in 1965. Facing increasing pressure for black majority rule, Smith defiantly responded, “Not in a thousand years.” Enter Henry Kissinger. (Yes, we can even learn from the vile, e.g., when McNamara later felt bad about Vietnam—or perhaps the genocide in Cambodia—Kissinger famously mocked him by pretending cry.)

The American strategy at this time was to increase African unity against outside influence of any kind, whether that be white minority rule or…Marxist threats to capital. But to do this Kissinger first had to deal with Rhodesia and the problematic Ian Smith. Leaders of neighboring countries feared a bloodbath was inevitable. For years the British had failed to successfully negotiate with Smith. Borrowing a term from Part 1 of this series, they were committing the Sir Galahad Fallacy, waiting until they sat down with Smith to “make their case”.

Kissinger instead focused on moves prior to any formal meeting, aimed at cumulatively pressuring Smith into altering his position. As quoted in Kissinger the Negotiator, when asked if he would also sit down with Smith, Kissinger replied, “I have no present plans to meet with Mr. Smith and this would depend entirely on assurance that a successful outcome of the negotiations will occur.” Kissinger developed an influence strategy leveraging the leaders of frontline nations, moderate African leaders, British diplomacy, and pressure exerted from South Africa.

As Kissinger networked and his view of the decision landscape evolved, he iteratively revised the influence strategy as he learned his way forward, ending with Smith moving from declaring there wouldn’t be black majority rule in a thousand years to agreeing it would happen within two.

The Middlegame

This is where you work your map to evolve the landscape in support of the decision you would like to have made. You cannot purposefully leverage a dynamic you are not aware of. Creating the map required you to think about and visualize the dynamics at play. As discussed last time, facts don’t influence, relationships do. To quote Michael Grinder, “By modifying our own behaviors we create our own success through relationships. And in so doing we influence the groups in which we participate” (from his book, Charisma, italics added).

To influence a particular decision, any decision, you need to learn whom the decision maker (the “D”) tends to listen to, whom these people in turn tend to listen to, and so on and so forth. This is Grinder’s concept of “permission”, of one person’s level of receptivity to another’s influence. In the influence map this is represented by the width of the relationship arrows.

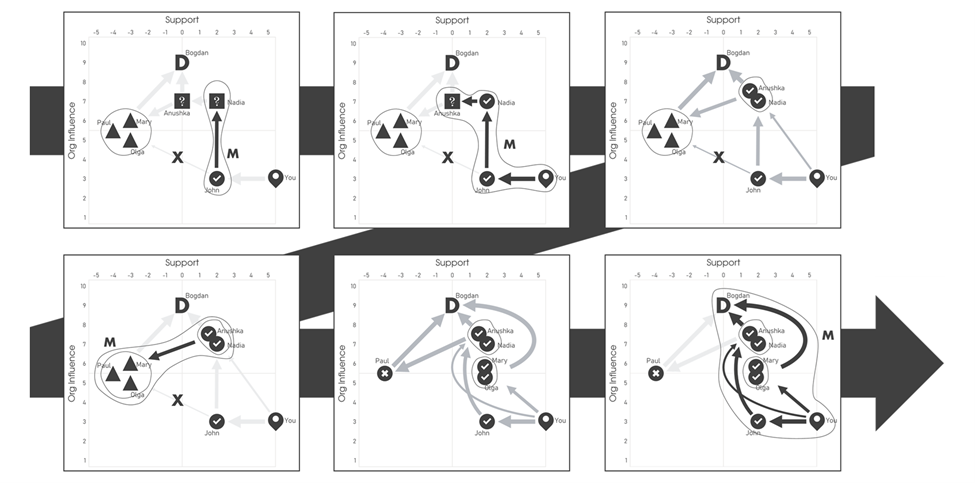

In the map above, for instance, there are only two high-permission paths to Bogdan, the D. One is Anushka. The other is the group of Mary, Paul, and Olga. They, you believe, also tend to listen to Anushka, forming a triangle. You don’t have high permission with any of them. Nadia does, however, and she also tends to listen to John, whom you already know is in favor of the decision you would like to have made. This suggests having John meet with Nadia on your behalf. If John is successful with Nadia, then you could have her meet with Anushka. Alternatively, you could have Nadia introduce you and John to Anushka and then set up a meeting with the four of you. Ultimately, you should do whichever you think is most likely to produce the desired outcome.

Nadia may have a better sense of which might go over better here and so should be involved in planning the next step. Let’s say all four of you meet and Anushka is on board with the decision. You then send her and Nadia to meet with Mary, Paul, and Olga. Mary and Olga say they will support the decision in question, enabling you to set up a meeting with Bogdan, Anushka, Nadia, Mary, and Olga, leveraging their combined wide paths to the D.

Now, notice how different this is from what we usually do. If you’re like me, then normally you would get on the D’s calendar and spend your time crafting the “perfect presentation”. This commits the Sir Galahad Fallacy. Presenting to staff, to senior leaders, to the D, risks ignoring whatever hidden dynamic is at play.

If the D has a history with the topic in question, then they likely have formed opinions and already made decisions on the topic. A formal presentation is not likely to get them to rethink things. This also ignores, as DeLuca points out, that higher-ups often have their own “mini-culture” surrounding such presentations, where certain personalities are essentially “holding court”. Often you will never learn what people really thought of your presentation, as ideas are often praised just to signal moving on from them.

Agreeing to present in this way poses a similar risk to consultants agreeing to pitch—you’re already giving much of your influence away! Instead, as illustrated by the Kissinger story above, it is better to focus on “away-from-the-table moves” that set the stage prior to any meeting with the D. Here, what you’re chiefly looking to do is broker the right conversations to meaningfully iterate the map. Since meetings are largely the medium of influence, it pays to be strategic about them. The effect of any series of meetings in part depends on their sequencing.

Every meeting you hold adds new information, corrects where assumptions might have been off, and indicates logical next steps. As Jean Boulton notes (see The Dao of Complexity), the more your assumptions accurately capture the way the world really is the more successful your interventions are likely to be. Such learning thus both alters the map and generates new options.

In considering how best to proceed, it can be helpful to consider the quadrants of the map, as shown below. As noted in Part 1, you are likely in the lower-right quadrant. The D is probably at the upper middle or upper left. To start working your map, you will typically start by enlisting people in the bottom right to help grow support in the top right.

In other words, do not go after the most influential people first. As you talk to people, some might immediately express their support. That’s great. Mark them as Coalition on your map. Others won’t be so easy. As our initial map above illustrates, you won’t always be the right person to do the influencing that needs to be done. That’s fine. Leverage your network’s network. Use the map to find the right people for the right meetings. Learn to send the right emissaries to create high-permission paths forward.

As you meet with people, it is important to remain open and firmly Socratic. You are not looking to “change people’s minds”. This is the wrong framing and approach. It implies they are “wrong” and need “correcting”. In fact, you’re not there to argue or debate anything—scoring points only loses goodwill and closes others off. You’re not there to convince people of some preconceived agenda handed down from on high. You’re there to build community, evolve a subculture of support around a larger aim, and hold the space necessary for the movement and exchange of ideas.

Remaining open here, as in “radical openness”, is a concept from bell hooks and her approach of “engaged pedagogy”. This provides us with better framing. Consider that you do not own the collaborative agenda. By staying always open to ideas and input, by assuming that if others do not add to the collaborative agenda that you are failing to optimize it, you will then enable the group to both maximize its cooperative impact and continuously improve its thinking. With this mindset you should be asking questions as though you do not already know the answer…because you don’t.

With this frame in place, you have nothing to be defensive about. There is no argument involved you are in danger of “losing”. So put your ego in your pocket—you don’t need it. You should want the agenda to change as the cooperative builds. By developing a more complex political vocabulary of the underlying system you will often uncover possible interventions that otherwise would have remained hidden. Thus, even your understanding of the decision you would like to have made will often evolve as you meet with more people. That’s normal. The target decision should not be set in stone. If you discover a more impactful goal and the group unites around it, that’s a good thing.

To be “Socratic” here is to genuinely listen and ask questions in a way that shepherds others along on a journey of co-exploration. Do more listening than talking and more asking than telling. In each meeting, learn about the other person. What is their agenda? What are they experiencing that they would like to change? What are the underlying issues they are facing? Encourage people to name their fears and frustrations. Actively listen and summarize what you hear. Invite others to do the same. Discuss what they haven’t had a chance to express elsewhere.

If there is a proverbial elephant in the room, name it! (As the old Italian saying goes, “Put the fish on the table.” If it stays hidden, it will stink.) Sometimes just calling something out that validates what others are experiencing will be enough to get them on board. This bouncing back and forth will help you better “paint the walls” of the box you’re in while also growing a subculture of raised awareness and self-determination. I find the table below helpful, adapted from Sobel’s Power Questions.

As you meet with people it is important to, as negotiators say, lead with agreement and mine for common cause. The more you dig into different underlying needs the more commonalities you will also unearth. This is valuable information! These commonalities point to potential larger outcomes. Paraphrasing Jesse McMullin, “To create more value you need to ask bigger questions.” Find areas where the other person’s issues can be linked to yours, creating a larger initiative with improved thinking and increased buy-in. This helps you to grow a community around a shared, collaborative agenda.

You should then share the credit for this larger agenda. If people claim credit for the ideas expressed in these meetings, great! This is what you want. As much as possible be sure to get others advocating on your behalf. In general, the more people you “right-shift” on the map the more high-permission paths forward there will be. Ask others to advocate for the combined agenda in their own meetings and report back to you. What they report can then also be used to update your map. After people report back, quote them in subsequent meetings.

Now be careful here. You’re looking to have questions asked and answered, and while you’re conversationally approaching others as your peer (something discussed more Part 3), there is still often a power dynamic at play. The prevailing culture, the “way things are done around here”, is a spinoff of the existing economic power base. To question the culture can be perceived as challenging this power base. If you’re inquiring about things customarily left unsaid, what James C. Scott dubs the “hidden transcript”, this might ruffle some feathers.

When you raise an issue, you should first want to hear what other people think about it. Don’t just dive in and lay all your cards on the table. Let what people feel safe sharing in part steer the conversation. In other words, check safety first and keep your foot out of your mouth. (When you have a foot in your mouth it hampers your ability to influence.) So instead of making blanket statements and plainly declaring your position on a possibly contentious issue, it is better to first ask people about their thoughts, views, and concerns. This reveals more about whom you’re talking to and how it is best to word things and proceed.

Now, one more caveat. It is easy to falsely believe you’re in alignment with someone when you’re actually projecting meaning onto what you hear them saying. This is a big no-no. We tend to assume that the words we use clearly map to the meanings we intend, that the signifier (word) and concept (signified) are a tight pair (a sign). This often isn’t the case. As Claude Lévi-Strauss first argued, our signifiers often “float”; they are untethered, and how we then collectively “tie them down” can be a site of political struggle (e.g., as strategist Ajit Maan notes, the news is less about informing us of what happened and more about buttressing a particular point of view).

Here is a great example: Both America and China adamantly believe they are more “democratic” than the other. Now, Americans might balk until they learn that, borrowing a concept from Jacques Lacan, how this word is “quilted” in each society makes them very different concepts. This equally applies to any corporate setting. It is easy to think you’re aligned with someone on the need to “become more agile”, that you need to “accelerate value” for “customers”, etc., but again, the devil is in the details. Be wary of weasel words (terms often left intentionally vague, like “value”) and zombie nouns (processes reified as nouns, like customer “delight”).

Thus, it is vital that you always unpack and co-explore meanings. This is the only way to avoid what we might call “illusory alignment”. We are always speaking in a sort of shorthand that only makes sense to us while simultaneously expecting others to read our minds. Thus, real alignment requires unpacking and co-exploration, active listening and summarizing. Differences in meaning and interpretation not surfaced will often lead to downstream inefficiencies, if not outright thrash.

To increase your politically savvy you should also seek to grow an awareness of your own “political risk”. Increase your self-awareness of behaviors that unnecessarily expose you to risk. These behaviors can be called “Slip Hazards”:

You might also find the image below useful (adapted from Marie McIntyre’s Secrets to Winning at Office Politics).

Now onward to Part 3.