This post concludes a three-part series on influence mapping. In Part 1 we covered creating the map. In Part 2 we discussed how to work the map to evolve the decision landscape to your benefit. In this post we will introduce some final principles, summarize, and make some concluding remarks.

Intro

David McKee’s children’s book, Three Monsters, is quite the little tale about diplomacy, negotiation, and influence. The book is, of course, about three monsters. The red and blue monsters laze about on a large island, complaining about how rocky it is. One day a yellow monster arrives in a small boat. His island was destroyed in an earthquake. He humbly asks if they would share their island with him.

Instead of agreeing, they verbally abuse him (they are monsters after all), calling him horrendous things like a “gormless gump”, “mustard face”, and a “custard-colored, cringing creep”. The yellow monster consistently responds diplomatically with things like, “your wonderfulnesses”, “most brilliant of monsters”, and “glorious kindnesses”. The red and blue monsters will still not let him move onto the island, but he can have all the rocks…which they want to get rid of anyway.

The yellow monster thanks them sincerely and begins removing the rocks. When he is finished, he asks if he should also level the soil for them. They say of course. They then suggest he also tidy the edge of the jungle. He does so, thanks them, and leaves…and they are shocked. Where is he going? With all the supplies they graciously provided him, he made his own beautiful island. They want to know if they can visit him. He says yes—if he can also visit them when he wants.

This is similar to one of Gerald Weinberg’s principles in The Secrets of Consulting. He calls it the “Buffalo Bridle”. The lesson is that you can make the buffalo go where you want… provided that is also where the buffalo wants to go. The yellow monster had his own agenda but had the presence of mind to listen for the pain points of the red and blue monsters. They were complaining about how rocky their island was. The yellow monster “mined for common cause”—that is the Buffalo Bridle in action.

The Endgame

Author Rick A. Morris observes that when you become a PM, you’re told the BIG LIE: “You own the product!” You quickly realize it’s not true. In fact, you don’t even have much decision authority. (What you do have is a unique risk of getting blamed for things.) Thus, Morris argues the No. 1 skill PMs should focus on is influence. I would extend this to other roles (not least of which is designer). Even when one does have formal authority, after all, influence is still crucial—attempting to mandate behavior change often just backfires anyway.

Real leadership, after all, is not a synonym for “executive”. It’s rather the ability to show a path forward in a way that inspires others to want to be co-travelers. To quote John C. Maxwell, “Leadership is influence, nothing more, nothing less.” Influence mapping is a key tool that helps you uncover your best influencing opportunities. As you grow your Coalition and increase the D’s exposure to the evolved, collaborative agenda, you will gain a sense of when and what the right meeting with the D will be—that’s the endgame.

This is similar to the Japanese concept of nemawashi, of “working around the roots”. Nemawashi happens in the informal discussions before a formal proposal, or ringi, is submitted for approval. In the end, you want to have grown an agenda that essentially sells itself; or, as Joel DeLuca puts it, the goal is to provide the D with an overwhelming “experience of convergent validity”.

DeLuca however emphasizes creating “51% support” (i.e., majority support) for your idea. The approach here begs to differ. Putting an issue to a vote and making a decision based on what you’re hearing are not the same thing. If the latter, which is more likely the case in my experience, then you don’t always need majority support. In fact, you could gain majority support only for the D to strike the idea down anyway, especially if the few people who have the D’s ear were not in your majority!

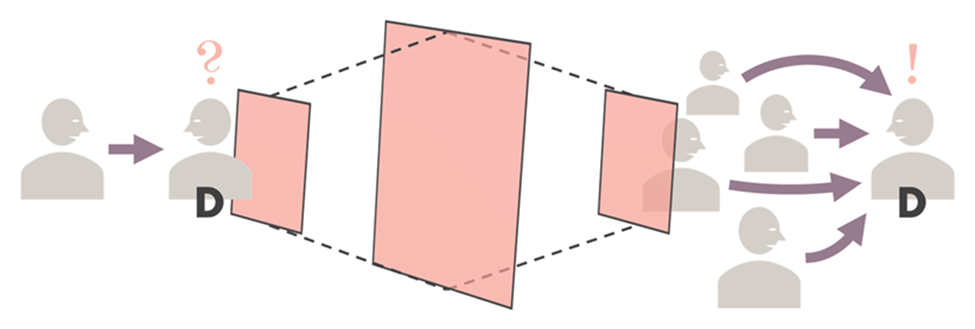

The present approach therefore relies more on Grinder’s concept of permission and the (perhaps counterintuitive) idea of removing yourself from the equation, which brings us to his concept of “contamination”. This is when you and the agenda become conflated in people’s minds, as easily happens when presenting to executives who are essentially “holding court”. If I go pitch to the D, then it becomes easy to see the agenda as just “Charles’ idea”, which means dismissing me in the meeting effectively dismisses the idea.

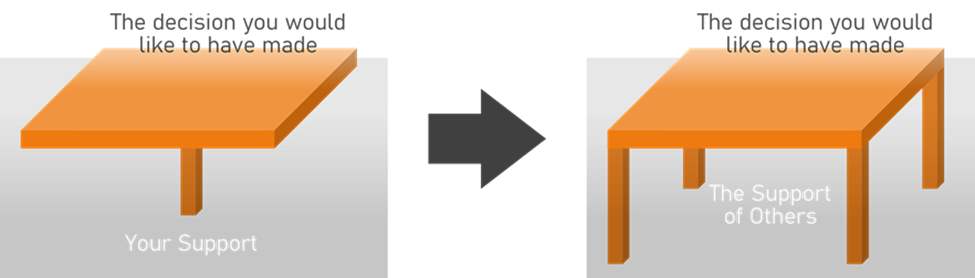

In other words, you should want to avoid conflating yourself with the agenda. Instead, you want as many people with the D’s ear as possible feeling they co-own the agenda and wanting to talk about it. You are ultimately trying to right-shift the D on the map. Sometimes this can be achieved without even meeting with the D. Or, if a meeting does occur, you might not actually need to be there. This can be visualized as a table.

As you go through the process of mining for common cause, growing Coalition around a collaborative agenda, and getting others advocating on your behalf (all principles from the last post), keep your WHAT and HOW flexible. This principle is from UN facilitator Allan Parker. Attempts to influence often fail when we focus on our WHAT (our agenda) to the neglect of our HOW (our approach). As Allan warns, if you find yourself justifying your ideas, being defensive, or blaming others for the lack of your success, these are red flags that you’re too focused on WHAT. If you need to alter your approach, then you should have the flexibility to do so.

It’s not about your habits and how you like to approach things. You must learn how your target audience would like to have their information and then ensure your autopilot isn’t running the show. The way executive coach Tom Henschel puts this, when people are looking to learn something, they already have a question in their minds—this is like a slot with a shape. If your answer doesn’t fit this slot, it will be rejected. If you sense resistance, then unpack it. Find out what is at its root.

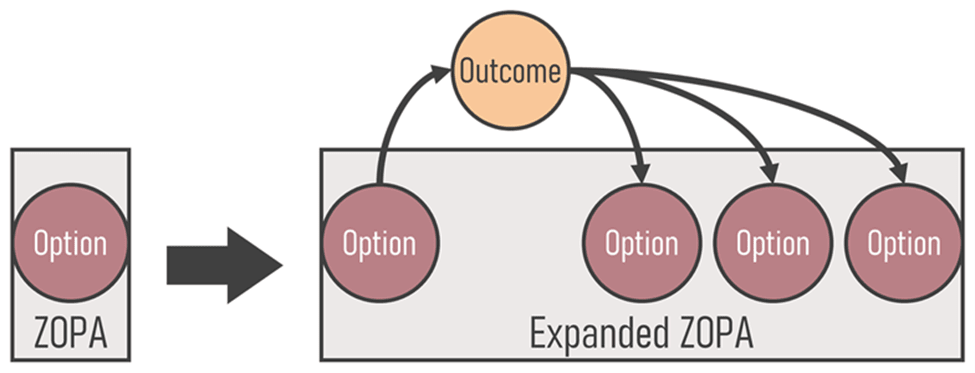

In Frame Reflection, authors Schön and Rein point out that your agenda—whatever it is—contains a narrative about what is wrong and what to do about it. Stakeholder disagreements are often more about the latter part, the solution ideas. These are akin to disagreements over “positions”. An important negotiation concept is to up-level from personal positions to the overarching interests they are meant to fulfill.

As described in Fisher and Ury’s classic, Getting to Yes, this expands your ZOPA, the “zone of possible agreement”. In a follow-up book, Getting Past No, William Ury elaborates that when someone disagrees with your lower-level position you should have the presence of mind to shift attention back to the ZOPA itself. You can often do this simply by acting as if the other person is trying to solve the same larger problem that would satisfy both of your interests. This neat trick enables you to reframe disagreement as collaboration.

In product work, this position-to-interests shift is often described in terms of output-to-outcomes, in terms of tying solution ideas (ideas about work output) to goals framed around what they are meant to achieve (outcomes). Eliciting such target outcomes can be challenging, but doing so creates a space to then explore alternative ways to achieve them. This helps you expand your ZOPA and further pull in Coalition. Solidifying agreement around more ultimate aims helps reframe the situation to the satisfaction of all parties involved.

Even if you largely disagree with what someone is saying, keep in mind that there is still a ZOPA. After all, you don’t have to be in total agreement with someone in order to join forces and fruitfully collaborate. If, however, you meet with someone who will not support the decision you would like to have made, that’s fine. Mark them as Opposition on your map, but don’t let it impact how you interact with them. Look for ways you can help them anyway. By building “Coalition” you are not establishing some kind of exclusive club.

Consider each conversation, first and foremost, as just being informational. Keep a good “listening boundary”. Whether someone ends up being Coalition or Opposition, you’re still learning. You’re still expanding your network. Even if they don’t support this decision, they might support the next. They might suggest you talk to someone else who ends up being instrumental. In the end, Opposition can still be of help. Unfortunately, the converse is also true—not all Coalition will ultimately be helpful.

Some may act like Coalition while also trying to obstruct you. As discussed in Part 1, it pays to be able to spot such “gatekeepers”. Sometimes, of course, there is a good reason for gatekeeping. Maybe it’s part of their role. Maybe it’s part of the current process and they’re acting as quality control. Maybe they are doing similar work and perceive you as encroaching onto their territory. If so, then they are Coplayers, not Opposition. If you do not gain their imprimatur and cooperation, then you might be asking for trouble. (To quote Erika Hall, “You don’t want your work getting trampled in a turf war you weren’t even aware of.”)

As you proceed, remember that every meeting along the way is just another conversation. If you aren’t treating them as such and focusing on relationship, then you’re probably putting your WHAT above your HOW, because a conversation is not sales pitch, it’s not a job interview, and it’s definitely not an interrogation. This carries an important implication we often forget. As John Sanford makes clear in his excellent book, Between People, (discussed here), conversations are egalitarian. This means several things, not least of which is that real conversations happen between equals.

Borrowing another concept from Michael Grinder, there is a difference between someone’s “position” and their “person”. If you’re just focusing on position, on rank or grade level, and not on person and relationship, then you’re not having a conversation. Alan Weiss has long pointed out that to be seen as consultative you must first believe you are peers with the person you are speaking with. If you instead show up ready to give your “very best pitch”, you risk coming across as needy. You risk losing respect. Yes, pay heed to the caveats called out in Part 2, but also be mindful of this important fact. Though there is likely a positional power dynamic at play, you should always seek, in as much as possible, to intentionally dismantle unnecessary hierarchies.

If you believe you are aligned with someone, double check! “Coalition” doesn’t mean you think someone is on board. Someone is Coalition if they have told you what key topics mean to them, have summarized the collaborative agenda in a way you agree with, and have verbally stated their support for this agenda. You need to gain a public statement of support from people, something you can quote them on and remind them of later. You’re looking to gather “sponsors”, not in terms of funding but in terms of people willing to lend you their status and clout.

Yes, you are going to namedrop them in meetings. Yes, you are going to suggest other Coalition members do the same. Yes, you are going to connect people to them to increase your “centrality” in this growing conversation hub. By the way, this isn’t “transactional” or “dirty” if you’re genuinely building relationships and organizing to effect positive change you really believe in. Ultimately, you should seek to add value for everyone you talk to and leave them feeling energized. Leave them feeling excited about the opportunity of collaborating on this. Leave them looking forward to meeting with you again. The bottom line is that people are people, and people like collaborating with people that they like.

Now, if some of this seems too “political” to you, then remember, whether something is really “Machiavellian” or not depends on whether you are being shady. If the people you are influencing would support everything you’re doing, then there is nothing “Machiavellian” about it. You are building relationships and adding value and, in trying to influence people’s decisions, you are also trying to improve them. There is nothing shady about it.

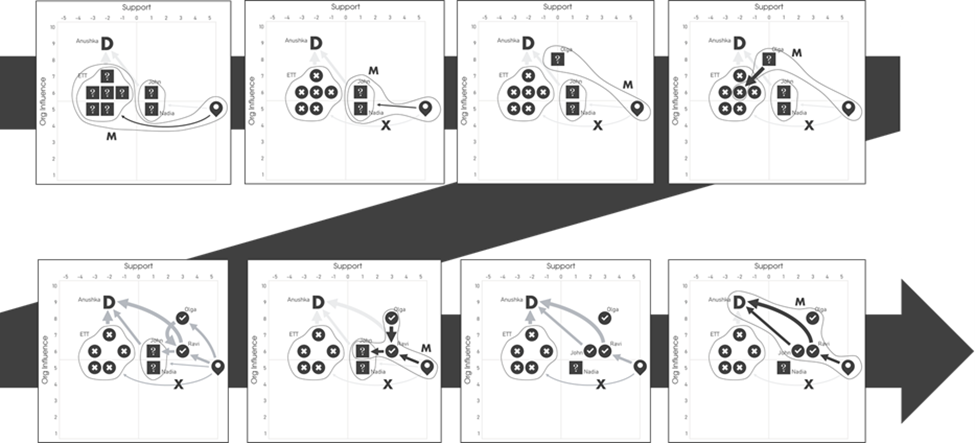

OK. Let’s look at a final example and then wrap. Sometimes the map will not show you where to start, in which case you just need to dive in. In the example below, Anushka is the D. You are aware of two groups with high permission with Anushka but have no idea whether they would support the decision you would like to have made. You decide to meet with the larger group. They are opposed. You meet with the second group. They are also opposed, but suggest you talk to Olga.

You meet with Olga. She declines to say whether she is in support of the decision but offers to chat with someone from the first group you met with. She meets with Ravi and reports back they will both support the decision. Ravi then suggests the three of you meet with John, as Ravi believes John will ultimately also support the decision as well. John agrees. You then set up time with Anushka, including Olga, Ravi, and John. Olga has high org authority and Ravi has high permission with the D, both assets you are leveraging by enlisting them into the chat with Anushka.

In sum, to influence a decision, any decision, you need to discover who has the authority to make it, who and what has permission to influence them, and then design the approach accordingly. This applies anywhere. In product work, for instance, any design, properly understood, is just decisions made. Influence is the currency. It’s all just conversation and the meetings are the medium.

If you want to up-level your impact, seek the most expensive problem you can influence. Influence mapping helps you grow Coalition and navigate the non-Coalition political landscape. There are many other tools that will also help your Coalition along the way, such as learning how to use strategy tables, build out a value mapping, and/or build out a visual strategy. You will achieve far more as a group than you will individually.

If this seems daunting, remember, you have to start with your actually existing situation. Further, you often won’t need as many people on your side as you think. Even if you’re trying to transform the thinking of an organization, Deming argued that “critical mass” for such change is only the square root of the size of the organization. Thus, following Deming’s reasoning, to transform the thinking of a population of 1K people, you would only need to build a Coalition of about 30 people.

Oh, and by the way, if you are often the D you should still want people applying these techniques. There is a saying in karate, “At the foot of a lighthouse it is dark.” You don’t see a lot of the problems directly beneath you. You should totally want your people collectively exploring big issues in their environment, considering options, and then coming back to you with their distilled, multiparty insights. That will improve the visibility of problems and improve your decision making. This increases your situational awareness.

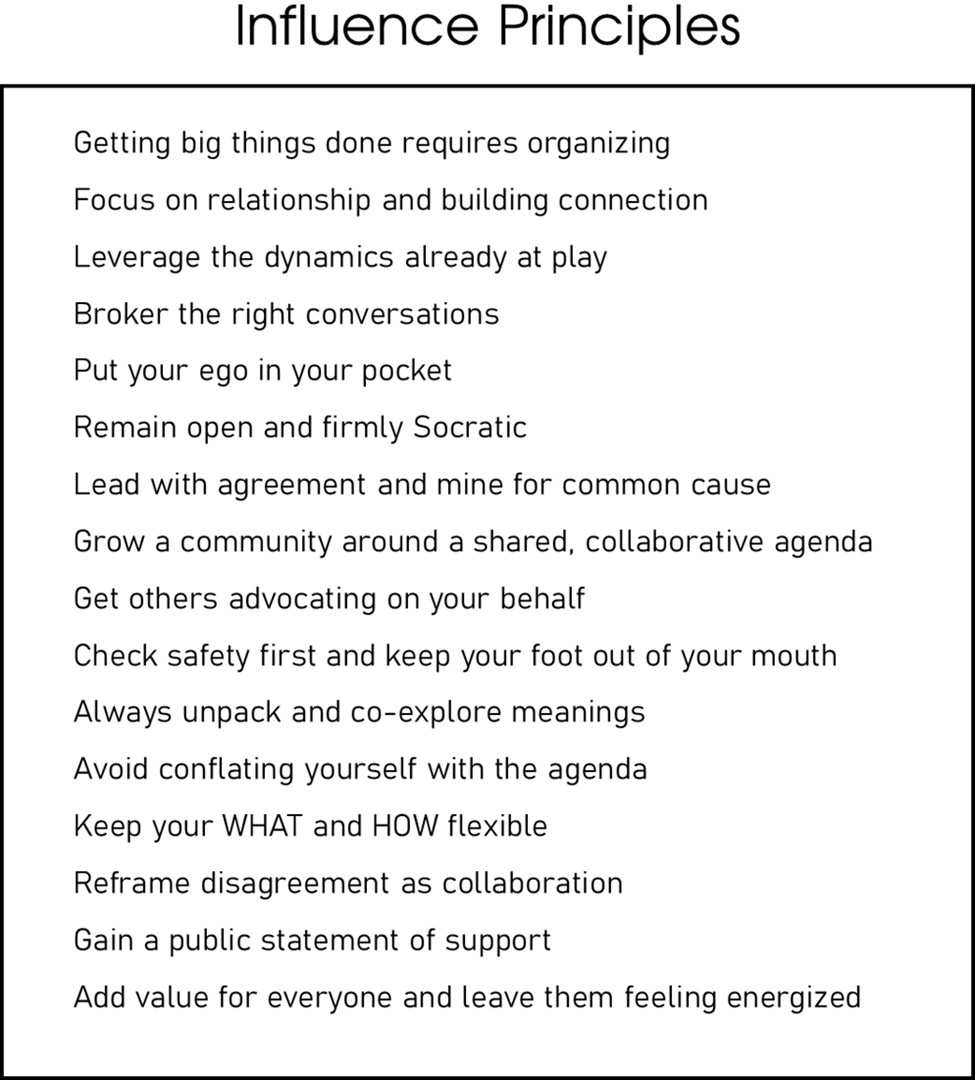

Thank you for reading. I hope this was helpful. In total, we covered 16 influence principles in this series, shown together below. Beneath that is another way of showing this, what might be called the “Iceberg of Influence”.

Until next time.

I love this series for its wealth of insight - thank you Charles!